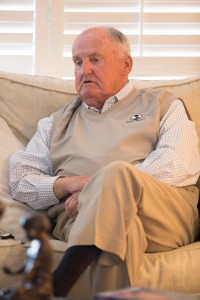

They call him a legend. He has a stadium and an ice cream flavor named after him. He was the fifth most winningest coach in NCAA history at the time of his retirement, yet he is as welcoming and approachable as an old friend.

LaVell Edwards coached BYU football for 29 seasons (1972–2000). He has been called the patriarch of BYU football. With 257 career victories, he is ranked as one of the most successful college football coaches of all time. Edwards was named the State of Utah’s Coach of the Century and inducted as a member of of the State of Utah Sports Hall of Fame. He was also named NCAA District 8 Coach of the Year eight times, Bobby Dodd National Coach of the Year in 1979 and AFCA National Coach of the Year in 1984. Perhaps his crowning achievement was coaching the 1984 National Championship team.

Edwards is now quite at his leisure. Just two years after he retired as a coach from BYU, he and his wife served a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New York City in the public affairs department.

While on his mission, a man who knew of Edwards’ background approached him to ask for some help in starting a football team in the nearby high school in Harlem. Edwards talked to the mission director about this idea. He said, “I didn’t go on a mission to get involved in football.” His director gave wholehearted endorsement, telling Edwards this would be a great opportunity.

Edwards helped get the team going, and they found that it opened many doors for missionary work and improved the attitude people had towards Mormons. Now there are a few wards there, and Edwards was part of that growth. Edwards loves that the Lord can use any means to move the work along, even something as simple as his own coaching background.

A favorite pastime for Edwards now is golfing. “I’m not that good, especially with my driver,” he said. However, he is known to have been an excellent golfer in his younger years. His age may slow him down, but he is still a regular at Riverside Country Club.

He said he loves having more time to relax with his family. His wife was always an anchor for him in his career and with the family. “Patti wanted me to be home. So, when I was home, I was home. I wasn’t stewing and fretting about how practice was or how the game went,” Edwards said.

Edwards grew up on a farm as the eighth of 14 children. “You always had someone telling you what you’re supposed to do. I was raised in that kind of atmosphere.” From a young age Edwards had many responsibilities on the farm. He said the hard work made him stronger. “It helped prepare me for my future,” Edwards said.

No one in his family had gone to college, but during his junior year of high school he decided he wanted to go to college. “And I just made up my mind that I wanted to be a football coach.” He got a scholarship to Utah State, where he played football, went into the military for a few years and started coaching a high school football team.

“I was born and raised in the church. As I look back, I think, we are all a product of how we were raised and the decisions that we make,” Edwards said.

Talking about how the gospel influenced him as a coach, Edwards said, “I think membership in the church allows me to make the kind of decisions that I make. It not only helps me in doing right and wrong, but it helps me in making decisions that are good when dealing with whatever I’m involved with.”

Edwards became head coach at BYU in 1972 and built the program quickly. Edwards said the Cougars had their greatest run from 1979 to 1984. They were always ranked, and their wins were in the double digits. BYU finished the stretch with a National Championship in 1984.

At age 84, Edwards can recall many of the details of his career. One story he shared was his memory of the 1980 Holiday Bowl, also known as the Miracle Bowl.

“Their score was 45 to 25 with under four minutes to play. We sent in the punter (because it was fourth down and many yards to go for a first down), but Jim McMahon (quarterback) wouldn’t let him go in.” BYU called a time out, and McMahon came to the sidelines and told the coaches they couldn’t quit. The coaches waved the punter off the field and sent McMahon back onto the field. BYU completed a pass for a first down. That drive ultimately led to a touchdown, closing the gap to 13 points. “I saw it and thought, man, we’ve got a chance,” Edwards said.

During the next play, the opposing team, SMU, got the ball and ran 50 yards for a touchdown on the first play. “Turned out that was the best thing that happened to us, because it didn’t take up any time on the clock,” he said as he chuckled. BYU then scored two unlikely touchdowns in a matter of a couple minutes. BYU was only six points behind. SMU had the ball and, with 13 seconds left, punted the ball, but it was blocked by BYU.

“Now, with three seconds left, McMahon went out and threw a long pass from about our 40-yard line. The gun sounded while the ball was flying through the air. It came down, and Clay Brown caught the pass right in the middle of two or three SMU guys,” Edwards reported. It was unexpected, and the team and fans went wild.

With the score tied at 45-45, an extra point would win the game. The kick was good, and BYU won the 1980 Holiday Bowl by one point, 46-45. It remains one of the most miraculous comebacks in college football history.

Edwards is known for his high-flying passing offense, but his journey there is a bit ironic. He was a single-wing offensive lineman at Utah State. He joked that he was hired by BYU because he was the only Mormon who knew the single wing.

“The general perception was that if you threw the ball only three things could happen, and two of them would be bad,” Edwards said.

Despite that background, when he became head coach, he determined to produce a passing offense. This brought wins — a lot of them. The Cougars were called “pass happy,” Edwards said, but they were seeing success, so it didn’t matter what others said.

He was one of the pioneers who changed the game of college football to the passing-heavy offenses now run by most teams. “We are definitely considered a team that got the passing popularized,” Edward said.

As a high school coach, Edwards had decided that to emulate good skills is fine, but to imitate is the greatest mistake.

“Ultimately, if you’re going to be successful, you have to be yourself. You have to do things the way you feel, the way you think they should be done,” Edwards said. This sounds like a good thing, but it is far from easy, particularly when people are young and are trying to make a name for themselves, he added.

When Edwards was asked what he’d like to be remembered for, he said, “I want people to remember me for the way I treated people, the way I worked with other people in a profession that had a hand in helping people realize their potential.”