The snow has melted and the sun has warmed up Utah County, making Utah’s vast water canal system even more vital. These canals serve to not only irrigate farmland but are also used as a source of power for various companies. Though these canals have served Utahns for years, they also pose a threat.

Three major canal breaks have occurred in the last 15 years, damaging homes and claiming three lives. The biggest problem with these canals is that there is no documentation of them. According to Sen. Gene Davis, D-Salt Lake City, “The state has no inventory of where they (canals) are, and where they flow.” It wasn’t until the recent session of Utah’s Legislature that a bill, HB370, was passed to start an inventory of all the canals throughout the state.

The real danger lies in the lack of data and mapping for these canals. Most homeowners are unaware of their dangerously close proximity to these water canals, which results in landscaping decisions that put their homes and even lives at risk.

The man assigned to the job of creating the inventory list of all the water canals covering Utah is Kent Jones, state engineer. Jones has until July 2017 to create a full list, and according to Jones, he is going to need those three years.

Jones estimated that there are anywhere from 6,000 to 7,000 canals in Utah that are unaccounted for. The Legislature has allotted the Utah Division of Water Rights $130,000 for two years to complete this list. That money will go to the hiring of engineering students who will assist in the documentation of these various canals.

The problem with these canals is that though they were originally constructed in rural farmlands, as the years went by, Kent said, “They get subdivided, and houses move in.”

This was the case with the Murray break last summer. Water filled multiple homes’ basements to the ceiling and leaked out through the windows. But, according to Kent, it wasn’t entirely the canal’s fault. The added factors of homeowners cutting into the hill where the canal flowed through, rodents creating holes in the walls constructed by homeowners, along with the imperfections in the canal structure led to the break.

Jones said, “Cities that are approving subdivisions — if they’re letting subdivisions come in right along these canals — the developer and the city probably ought to know what’s happening there, and they ought to inform the canal company, and there ought to be some interaction.”

Utah passed HB298 in 2010, which stated that if a city was planning on creating a subdivision on the land that was within 100 feet of a canal alignment there had to be a meeting set up with the canal company.

That seems easy enough to abide by, but Provo’s river commissioner, Stan Rogers, said, “They were all put in in the 1800s …When they (canals) were put in … so they (canals) were not recorded.” Thus, planners may be unaware of canals on the property.

Not only is the list of canals nonexistent, but the state of the canals is private. Kent Jones said, “Canal companies are very concerned about letting people know they’ve got problems on their canals.”

In 2010 HB60 was passed, which required all canal companies to inspect their canals and come up with management plans for problem areas. However, these companies only had to let the Board of Water Resources know the plan had been formed; their documents of the process were protected.

The biggest reason these documents have been kept out of public records is because the liability associated with acknowledging that these problems exist with the canals is high. Insurance companies would cease to cover these canal companies, or the insurance would become so expensive that people would be unable to afford to farm or use the water anymore. Jones said, “I think at some point those documents will not be protected and they will come out into the public.”

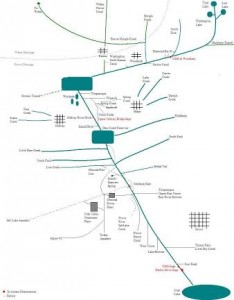

Many of Utah’s canals still flow through rural areas, but many have close proximity to heavily populated areas, according to Sue Odekirk, an employee of the Field Services Department for Utah’s Division of Water Rights. Odekirk deals directly with Provo and Orem’s canals. The Provo and Orem metropolitan area has seven larger canals operating within its boundaries. In fact, according to Rogers, “The one (canal) that would do the most damage if it were to break is the Provo Bench canal because it sits right on the side of a hill next to some expensive homes.”

Currently BYU and the state hospital in Provo are the biggest users of these canals, but they now use canals that have been moved into pipes. According to Sydne Jaques, a consulting engineer who has done community relations with the canals in Provo, “It is important for us to create an inventory of all the canals in Utah because they are each a piece of a larger water system. The more information we can gather to document not only where the canals are, but to also eventually collect data about the flows and the water usage, the better we can manage our entire systems and conserve water.”