The popular science fiction novel “Ender’s Game” started as a short story in 1977 and is scheduled to debut as a movie Nov. 1, starring Harrison Ford and Ben Kingsley.

The book, by BYU alumnus Orson Scott Card, is set in a futuristic culture where the government breeds genius children and trains

them as soldiers to prepare for the next attack by a hostile alien race. The novel claimed Nebula and Hugo awards — prestigious in the science fiction genre — and is on the Marine Corps reading list because of the leadership principles the book teaches.

Also compelling is the years-long process that led to the film’s development. Card, a co-producer of the film, fielded questions from The Universe as the scheduled Nov. 1 movie release approaches.

Q: Have you, or have film studios, wanted to make “Ender’s Game” a film before now? Why did you choose now to make the film?

A: We’ve been working on this movie for many years. Chartoff Productions, with Lynn Hendee as the producer who worked most constantly with me, optioned “Ender’s Game” more than 15 years ago. I wrote many scripts, with their counsel, and we took it to studios and possible producing partners many times.

The problem was that despite the visual strength of some of the scenes, the book is very hard to film. It takes place through Ender’s point of view — in the book, you always know what Ender is thinking. But a film can’t get inside a character’s head. So even if you show the scenes, it doesn’t mean the audience will like or care about the character.

We found that people who knew the book already would read my scripts and say, “Wow, you nailed it.” But someone who had never read the book would read the same script and didn’t understand what all the fuss was about. It wasn’t until my final attempt that I finally understood how to make it work.

The story wasn’t about Ender vs. the aliens, or even about Ender vs. the adults. It was about Ender with the other kids — helping them, caring about them, showing an example of strength and courage, and never acting for his own benefit at their expense. I realized for that to work, the script had to make the audience want to have Ender as their leader — not because he was so smart, but because they could trust him completely.

The script that had that idea at its heart worked. But that is not the script that was filmed. The director, Gavin Hood, shot the script he wrote himself, without reference to mine. That is not a surprise — executives can lose their jobs for filming an author-written screenplay.

I had my personal education in screenwriting, though, and more to the point, my personal exploration of my own book and what worked in it. So this spring, as I wrote the audioplay version of it — a six-hour miniseries for voice actors called “Ender’s Game Alive” — I didn’t have to go through the long learning curve. I knew how to adapt it. Of course, it’s a completely new script because the needs of audio drama are absolutely different from film scripting.

But I think when Audible.com releases the Skyboat Road production this fall, audiences that give it a try will find that yes, you can have a complete dramatic adaptation of “Ender’s Game” despite the inability to get inside Ender’s head. Of course, I had six hours to work with; the movie has less than two.

As for the movie: It got made when it did because there were finally studios willing to bet some serious money on making it work. First Odd Lot Productions came in, partnering with Digital Domain; then Summit brought in the rest of the budget. In midstream, Summit was bought by LionsGate.

I have to say that the LionsGate executives have been absolutely brilliant in their support of a production that they didn’t actually choose to do. I’ve seen a rough cut, and while there are changes that will annoy some fans, it’s a sharp, tight, emotional movie that contains much of what works in “Ender’s Game.”

Best of all, the movie doesn’t erase a single word of the book. So people who first encounter the story in the movie can always turn to the book to get the whole thing. And those who see only the movie will still have had a good time in the theater. Harrison Ford, Asa Butterfield, Ben Kingsley, and all the other kids and adults do a fine job in their roles, and the designs look great.

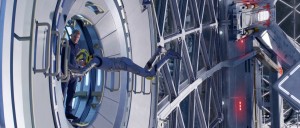

I think the special effects and acrobatic teams did the Battle Room as well as it can possibly be done. Good thing, too, because the kids about killed themselves learning how to make the moves on wires that the Cirque de Soleil professionals taught them to do. I bet they wished more than once that there had been a way to really film it in freefall.

Q: What are your responsibilities as a co-producer of the film?

A: My work as co-producer was all done in the early stages. Once Gavin Hood took over, my help was no longer required.

Q: Was the screenplay written exclusively by you or was it a collaborative effort with other writers?

A: The screenplay you see on the screen was 100 percent Gavin Hood. None of my writing was used. That was the decision that Odd Lot and Summit made; it was their money at risk, and they invested in the writer they believed in. I have no complaints.

Q: The narration in the novel gives insight to Ender’s motivations without him having to speak. How were you able to translate that form of narration into a screenplay?

A: It can’t be done. Novels are a completely different art from screenwriting. So translating a novel to the screen is insanely difficult. You have to make a new work of art that tells the same story using a completely different tool set. I think it has been done perfectly only a few times. I think of Emma Thompson’s great script for “Sense and Sensibility.”

It’s Austen’s story on the screen — but making superb use of techniques that film can use that novels can’t. At first glance, you think, Well, Thompson only filmed what Austen wrote. Then you realize — no, some of the best scenes are passed over in the book with only a paragraph or two. Thompson had to equal the English language’s greatest novelist, Jane Austen, in the wit and power of her dialogue — and she did it.

With “Ender’s Game,” we’re most definitely not dealing with the greatest novel or novelist. But “Ender’s Game” is far more interior than anything Jane Austen ever wrote, because the novel form has evolved since her day to concentrate on precisely the aspects of storytelling that film and television can’t do. So if anyone has criticisms of the script they shot, they should keep in mind that the job is nearly impossible in the first place.

Q: The novel addresses moral questions concerning the training of children and the extermination of an alien race. How will those issues be addressed in the film?

A: Come now. I don’t answer questions like that when students write to me asking, “What is the theme of ‘Ender’s Game?'” and I won’t answer them now, either. The novel doesn’t answer those questions, anyway — rather it raises them, and if anything it shows that the best you can do is muddle through, trying to do what’s right, as far as you can figure out what that is. That’s all that human beings can ever do. Even the great ones like Lincoln and Churchill are right only some of the time. Ender Wiggin, though fictional, is no better — because nobody ever has all the information they need in order to make a perfect decision in any case, let alone in every case.

Q: Will this affect the future of your writing career? Will you spend more time on screenplays or continue mainly with novels?

A: I make my living from fiction. To me, that is the finest storytelling medium ever designed. Even when a person aspires to screenwriting, television is the place where writers have the most freedom and the most influence over the final product. Most screenwriters labor on many scripts and see few, if any, make it to the screen — and even then, their work is usually at least partly undone by others. So in writing fiction, I have an unlimited effects budget, I can use all the locations I want, the cast is always superb, and nobody can come in after me and cut or reshoot scenes they don’t like.

For good or ill, when I write a novel, it’s written — unless I come back myself to fix it. I made a stupid mistake near the end of one of my novels. Fixed it in the paperback; we’re fixing the audiobook right now. Just a small revision in the last half of the last chapter. But such a howlingly dumb error. I was tired. And in my defense, nobody else caught it, either. Ever. But I did, and I couldn’t write the next book in the series till I fixed it. So yeah, even my fiction isn’t the final version.

I’ve written Valentine’s and Ender’s meeting after the war three different ways, in “Ender’s Game,” “Ender in Exile,” and most recently in “Ender’s Game Alive.” Which is the real one? Maybe someday I’ll do a new edition of “Ender’s Game” that reconciles them all. What matters is that in each case the scene does the job it needed to do. The characters are true to themselves, and each scene works within its context. That’s all I can ask a scene to do. After all, you do know that I just make this stuff up, don’t you?