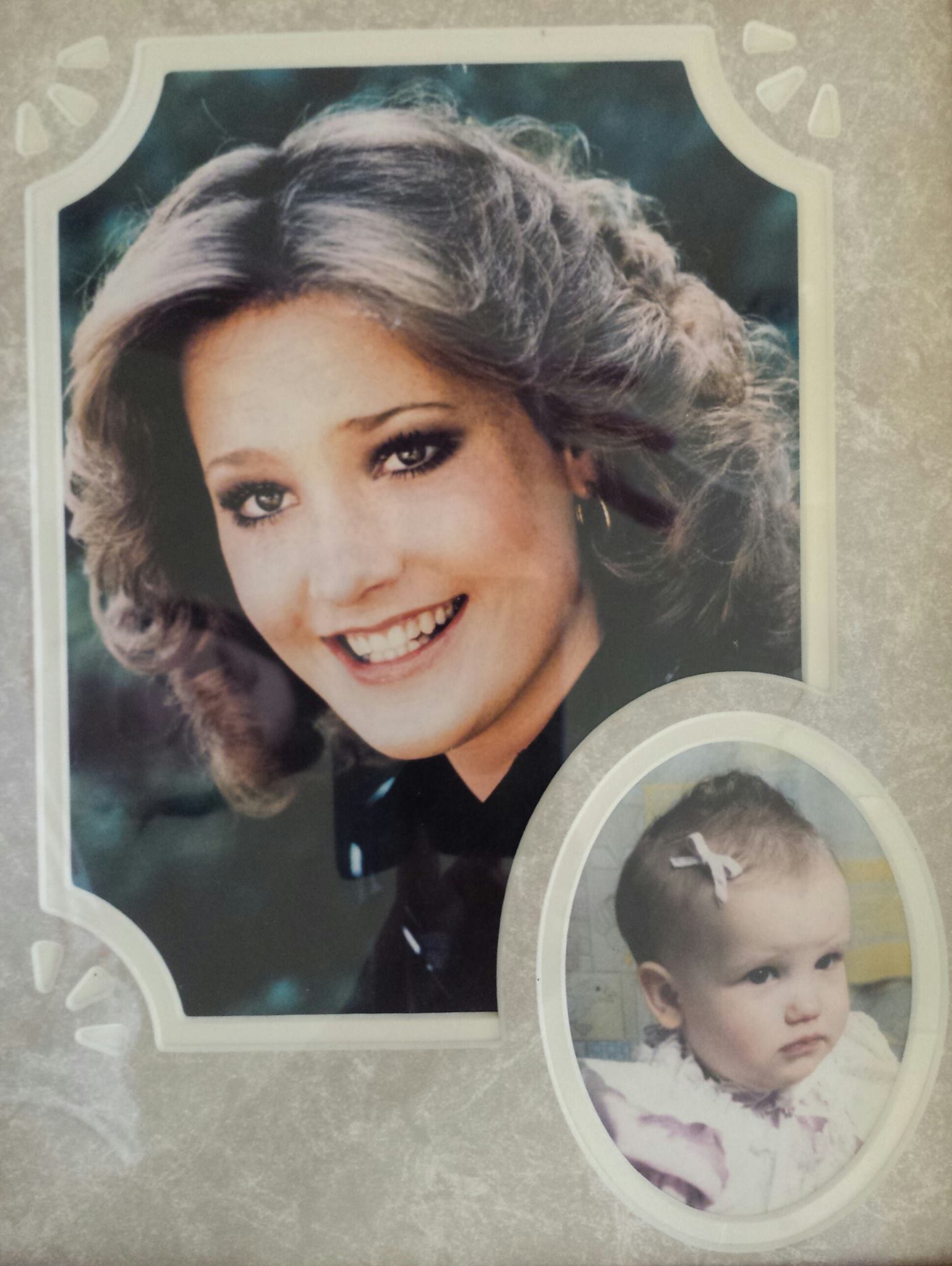

Forty years ago this April, Brenda Wright Lafferty walked across the stage at her graduation from Brigham Young University to receive her degree in Journalism from the Department of Communications. During her time at the school, she anchored for the student news production, then known as Week Night, and dreamed of becoming the next Diane Sawyer.

She married mere days after graduating and became pregnant within months; soon, she’d give birth to a baby girl, Erica. Independent, aspirational, and described as a Farrah-Fawcett-esque beauty, Brenda was entirely sure of what she wanted out of life.

So were her two brothers-in-law, Ron and Dan Lafferty. So sure, in fact, that they murdered Brenda and 15-month-old baby Erica in their American Fork home in the afternoon of Pioneer Day in late July 1984.

Enlarge

The case gripped the community and the nation: Ron and Dan had joined a fundamentalist sect known as the School of the Prophets. The School considered itself a breakoff of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the dominant faith of the region. Marked by anti-government sentiments, tax evasion and polygamy, the sect became the brothers’ obsession. Alan, Brenda’s husband and the younger brother of Ron and Dan, was minimally involved with the group, perhaps at least partially thanks to the discouragement of his mainstream Latter-day Saint wife.

Ron and Dan’s wives, nauseated by the prospect of polygamy (including Dan’s intention to take Ron’s underage stepdaughter as a plural wife) and suffering in their marriages, eventually left the brothers. Ron’s wife fled with the help and encouragement of Brenda.

Soon after his wife’s exodus to Florida, a depressed and anxious Ron announced he had received a “commandment from God,” which ultimately became known as the “Removal Revelation.” He claimed God required the immediate “removal” of Brenda and her child in addition to two local Latter-day Saint leaders who helped Ron’s wife leave.

Enlarge

The brothers fulfilled their “prophecy” by driving to Brenda and Alan’s home in the early afternoon of July 24, 1984, while Alan was at work. The pair forced their way into the home and slit the throats of mother and baby, nearly decapitating the child. The struggle was fierce enough that it knocked a painting off of the neighbor’s side of a shared duplex wall and loud enough that those neighbors chose to leave the duplex without stepping in or calling the police.

Sharon Wright Weeks was nearly sixteen at the time of her sister’s death. She’d just made the cheerleading team and had spent the day cliff diving near her hometown in Idaho. When her family’s brick home was awakened by her father’s ear-shattering scream in the early morning of July 25, 1984, no family member knew what the next few decades had in store.

Enlarge

They were promised justice by well-meaning prosecutors who intended to exact the highest punishment Utah state law allowed: the death penalty. Instead, they suffered through decades of trials and re-trials, sentencings, and appeals, all for Ron Lafferty to die of natural causes on death row in 2019. Brenda and Sharon’s father, Jim, passed out in court while listening to Dan testify, in excruciating detail, of the torture Brenda experienced leading up to her death. The family never saw the justice they were looking for.

Click through the case

Timeline: Amy Griffin

The case for the death penalty

According to legal scholars, the argument for the death penalty has traditionally turned on two points: deterrence and retribution. Deterrence encompasses the idea is that a potential criminal, knowing the possibility of facing the death penalty for their crimes, would be swayed from committing a crime in order to avoid the sentence. Retribution, on the other hand, is punishment, and meant to serve the loved ones of the victim, providing them with closure and justice—a life for a life.

Yet these oft-cited motivations aren’t tried and true. “There have been many attempts to study whether the death penalty deters crime, and the results have all been mixed,” said Stephanie Plamondon Bair, a professor of criminal law at the J. Reuben Clark Law School at BYU. She said there isn’t any strong evidence that capital punishment actually deters crimes.

Retribution, on the other hand, is more nuanced. “There might be an argument for keeping it for these types of extreme cases as a means of exacting retribution and sending an expressive message that there are certain types of behavior that we as a society will not tolerate,” Bair said, “even if that message doesn’t have an actual deterrence effect.”

Bair’s colleague at BYU, Justin Collings, calls this the “expressive function” of the death penalty. “It signals just how heinous our society regards some actions to be—and it might provide some kind of catharsis for the families of victims.”

A voice for change

“Until I heard her story, I’d never thought about the perspective from the victim. She was so emphatic and it really made me study about what was happening. It made me realize how broken the system is.” Rep. Lowry Snow, R-St. George

In the years since her sister’s murder, Weeks has worked with numerous groups to change the face of Utah’s criminal justice system. At first, she worked with local lawmakers to make the murder of a child a capital crime. Later, as she lost faith in Utah’s capability to actually execute convicts, she began to rally support against forcing Utah families to go through the painful process the Wrights had suffered through. In trying to find Utah lawmakers willing to hear her out, she cold called dozens of politicians to no avail. Yet when she arrived at her Utah House representative’s door, she found a willing—if initially skeptical—ear.

Rep. Lowry Snow, R-St. George, was a recent graduate of BYU himself when he first heard of Brenda’s murder. He’s traditionally been in favor of the death penalty—but something about constituent Weeks’ experience made him change his mind.

“Until I heard her story, I’d never thought about the perspective from the victim,” Snow said. “She was so emphatic and it really made me study about what was happening. It made me realize how broken the system is.”

Snow isn’t blind to the two recent legislative efforts to abolish the Utah death penalty that never got off the ground. Yet he’s confident that this time, the legislators will see reason. He believes if his colleagues are “careful and deliberate” in their thinking, “maybe Utah can help lead the way.”

He’s not the only Utah government official rethinking capital punishment policy. Utah County Attorney David Leavitt recently joined three other county attorneys in Utah to pledge not to seek the death penalty in any further cases.

“It’s time to change course,” Leavitt said in a press release Sept. 8 announcing his decision. “There’s a better route, and we’re going to seek it.”

The proposed replacement

The road to the death chamber is a long one. “The first and most important step is that the state has to put forward a case,” said Bair. “[They have to] convince a jury that the accused is guilty of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Once a defendant has been convicted, a separate jury decides whether to impose the death penalty. In Utah, that jury has to be unanimous in their decision, otherwise the offender receives a life sentence.

After a death sentence is handed down, “the convict can appeal both the conviction and the sentencing decision to the Utah Supreme Court,” Bair said. The defendant may also be able to appeal through the federal court system. With sometimes large amounts of necessary discovery and paperwork in between court dates, Bair said, the process “can take many years.”

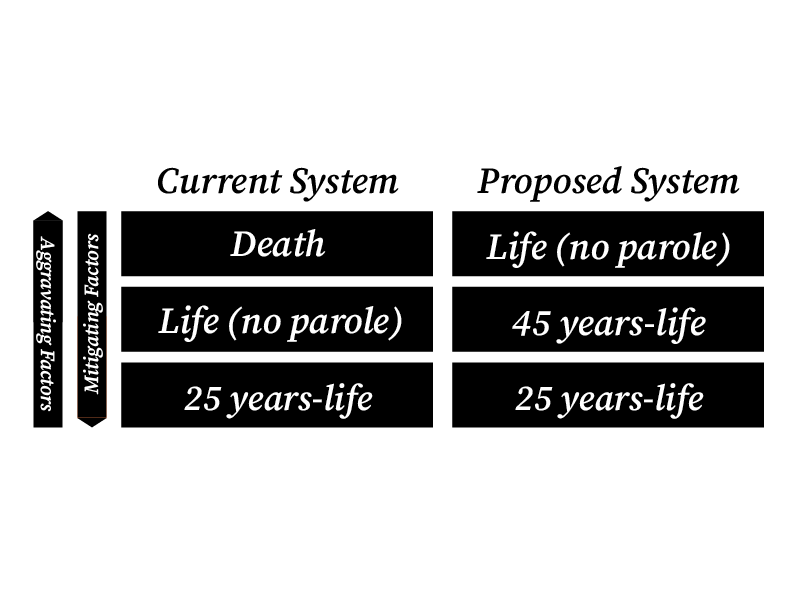

At present, capital cases typically have a three-tier punishment scheme: the death sentence, life without parole or 25 years to life with the possibility of parole. It’s for that second jury to decide which tier a convicted felon should receive in a capital case. This depends on aggravating and mitigating factors.

Snow’s bill, which is branded as a “repeal and replace,” is meant to take the death penalty off the table from the get-go for any future capital cases. Instead, the most severe sentence a person could receive would be life without the possibility of parole. The legislature would add an option of 45 years to life without the possibility of parole, which isn’t currently available to prosecutors. The bottom tier, which carries a sentence of 25 years to life, would remain intact. The addition of the 45 years to life sentence allows prosecutors to have multiple bargaining chips at their disposal when encouraging a defendant to plead guilty or testify in another case.

Source: Rep. Lowry Snow. Graphic: Amy Griffin

The new system could massively reduce court costs to taxpayers, according to the Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice. A significant portion of the taxpayer burden comes during the unique sentencing trial in capital cases. Discovery can go on for years in order to dig up anything that may point towards the convicted being less-than-totally-responsible for their crimes, which would disqualify them from death row.

Realistically, Snow sees the top tier—life without the possibility of parole—as itself being a sort of “death sentence,” imposed by Mother Nature rather than the state. This is important, Snow said, because “if there is a mistake, at least there is the opportunity to fix that. When it comes to taking someone’s life, there’s not really room for any error.”

"When it comes to taking someone’s life, there’s not really room for any error." Rep. Lowry Snow, R-St. George

The point of no return

The Bill of Rights requires “due process,” the idea that the state needs to be very careful before taking away anyone’s “life, liberty or property.” The Due Process Clause is found in both the Fifth and 14th Amendments, applying to the federal government and state governments, respectively. It’s supposed to ensure the government follows its own laws and only punishes fairly. It’s a big part of the reason why criminal trials take so long—the Constitution requires detailed attention & scrutiny before anyone’s rights can be taken away.

Due process doesn’t just include the initial trial; it also means if new evidence is later presented that may prove a convict’s innocence, there’s a chance to have that evidence considered. The problem that may arise with the death penalty is that there comes a point when the person is actually executed, which means if later evidence appears that proves the defendant innocent, the defendant is already six feet under.

The modern process of getting to the execution chamber is arduous, involving multiple court days, two different juries, and a multi-leveled system of appeals. Judges, juries and attorneys carry out this process that is intended to serve as “close scrutiny”. By the time the defendant gets to last rites, there shouldn’t be any question that the person with the priest is the guilty party.

"Far more frequently, and particularly with people of color, innocent death row prisoners were convicted because of a combination of police or prosecutorial misconduct and perjury or other false testimony." Robert Dunham, Executive Director, DPIC

Yet the numbers under that system aren’t particularly pretty. “The Innocence Epidemic,” a 2021 special report by the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), found that one person is exonerated for every 8.3 executions carried out nationwide. Since 1973, 185 individuals have been released from death row. When non-capital cases are added to the roster, the numbers are staggering: the National Registry of Exonerations reported in June 2021 a total of 2,795 exonerees who collectively spent 25,004 years in prison for crimes they didn’t commit.

DPIC’s 2021 report contains damning findings. In the press release accompanying the report, DPIC’s Executive Director, Robert Dunham, is quoted as saying that most wrongfully convicted people on death row aren’t there by accident.

“Far more frequently, and particularly with people of color, innocent death row prisoners were convicted because of a combination of police or prosecutorial misconduct and perjury or other false testimony,” said Dunham.

DPIC’s research found 69.1% of exonerations since 1973 were wrongfully convicted due to misconduct on the part of police, prosecutors or other government officials. Such misconduct was found to be much more likely in cases with defendants of color, cases with long appeals processes and cases with DNA evidence proving the defendant innocent.

A Catch-22

Even assuming that someone waiting on death row is, in fact, guilty, the journey to retribution isn’t a smooth one. Snow sees a stark disparity between what the victim’s family is promised and reality.

“A death sentence was imposed,” Snow said. “The [Wright] family was told by the prosecutor, ‘This person deserves to die, and we’re going to get the death sentence.’ But it took 35 years and we still couldn’t get it done. The perpetrator end[ed] up dying in prison.” That kind of time weighs on the families of victims.

The typically decades-long road to execution is, at once, what saves capital punishment and what may be its eventual downfall. It’s necessary to be careful with an individual’s life, so a lengthy appeals process is constitutionally required. Yet the years of court proceedings are extremely painful for the family of the deceased. According to the Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice, the process is incredibly expensive to the state. During the period from 1997 to 2016, $40 million was spent on these appeals, which resulted in just two death sentences.

Snow calls it a “Catch-22,” saying that if a state tries to shorten the process in an attempt to get swifter justice for the family and cut costs for taxpayers, the sentence would be quickly reversed by a higher court “based on the fact that [the state hasn’t] given sufficient due process to the accused.”

It’s clear the criminal justice system is riddled with problems—on that point, there’s agreement on both sides of the political aisle. With proposed legislation in Utah and other states, each side also might soon be able to agree on whether the state should be killing people at all.

From the womb to the tomb: the conservative wave

"You know, it’s hard to be pro-life and to be pro-death. That caused me to do some self-introspection about what I believe, what I stand for. And so for me, it’s pro life from the womb to the tomb." Demetrius Minor, National Manager, CCADP

Traditionally, conservative voters favor the death penalty more often than liberal voters. “Utah is a very red state,” Bair said, “which could help explain why it has been slow in its efforts to abolish the death penalty compared to other states.” Bair also speculates that there could be a religious or cultural component, citing many students in her criminal law classes who believe “principles of justice and penance for one’s sins” justify capital punishment.

Yet Bair sees movement in the future. “There has been a steady shift in public opinion about the death penalty over the past few decades,” she said.

Demetrius Minor is perhaps reflective of this change. In 2006, Minor was in the initial stages of his entry into politics. He’d sat down with his pastor to have a conversation about their beliefs on abortion when the conversation turned to the death penalty—and his pastor said something Minor wouldn’t soon forget.

“He just said, ‘You know, it’s hard to be pro-life and to be pro-death,’” Minor said. “That caused me to do some self-introspection about what I believe, what I stand for. And so for me, it’s pro life from the womb to the tomb.”

Minor is far from alone in his opinion shift about the death penalty. He is the new national manager of Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty, an entity of Equal Justice USA. The group represents a movement to make conservative voters aware and informed of the death penalty, including all of its consequences and ramifications—and ultimately see capital punishment abolished. According to Minor, support for the death penalty among Republicans is already waning.

He encourages those in his party who still support the death penalty to take a deep look at what it entails. “There’s a lot of racial biases when it comes to the death penalty,” he said. “A person of color who commits a crime [against a white person]… [is] more likely to face the death penalty charge than a white person who commits a crime against a person of color.” This might come as a result of bias on the part of the prosecutor who made the decision to pursue the death penalty or the bias of the sentencing jury, or both.

Beyond the injustice in sentencing severity, Minor is also concerned about the court system’s general ability to get any given conviction right. “The death penalty is the only punishment in the U.S. that’s irreversible,” he said. “We’ve seen innocent people be put to death.”

He points out that capital punishment should be a sticking point for fiscal conservatives, too. “The cost is 10 times more than non-death-penalty costs,” he said, attributing much of the extra cost to additional lawyers, witnesses, experts, a longer jury selection process, and more pre-trial motions. “Just the economical and the emotional tasks that are assigned to the death penalty make it an antiquated practice…something that is not consistent with conservative values.”

The path forward

For Sharon Weeks, the work continues to ensure that no other families will have to go through what she has. Her mother died in 2016 without any closure on Ron Lafferty’s case. Lafferty wandered his way through the state and federal court systems, appealing on different aspects of previous trials and his own mental state. At one point, a question about a bloody drape held up the process for over a year.

"I want to put the heat under them a little bit. They’re in the hot seat. They’ve fallen a little bit short, but I know they can do better." Sharon Wright Weeks

The debate wasn’t a whodunnit. Dan Lafferty testified at one point that he would dig his sister-in-law Brenda up and kill her again if he had the chance. Yet still the case meandered through the system, dragging the Wright family along with it.

Weeks has dedicated her adult life to changing the system however she can. She speaks to the press, is active on social media, worked with Jon Krakauer on his book about the case, titled Under the Banner of Heaven, and is participating in an upcoming television drama miniseries based on the book, which will star Andrew Garfield and Daisy Edgar-Jones. Weeks does it all to get people to think about the issues—especially lawmakers.

“I have faith in my leadership in this state,” she said. “I love Utah.” She has a message for those in the legislature who have ignored her call for justice in taking on the death penalty.

“I really feel like Utah needs to be held accountable,” Weeks said. “I am going to name every single person that votes against this.” From her perspective, “there [aren’t] any more excuses.”

“I want to put the heat under them a little bit. They’re in the hot seat,” she said. “They’ve fallen a little bit short, but I know they can do better.”