After 29 years as an orchestra teacher at a public school, Samuel Tsugawa was told to go to the high school auditorium one evening. What he thought was a dutiful visit turned out to be a surprise concert in his honor. Students from throughout Tsugawa’s career gathered to honor his retirement from public education.

“I wasn’t the most important thing,” Tsugawa said. “I was the agent that gave students the gift of music. Music did the rest. They still played well, even after 20 years. They gave me that gift, and I’ll never forget it. I offered them the opportunity to be musicians, play music and make music a part of and improve their lives.”

The surprise concert was a rewarding moment in an occupation filled with challenges. For Tsugawa, it was proof that even with the challenges and barriers placed in front of students in regards to the arts in education, those who received the opportunity still felt the impact 29 years later. It was a rare moment for everyone present to see the long-lasting impact that arts education has on students.

Dr. Samuel Tsugawa teaches music education at BYU after 29 years as a public school orchestra teacher. (Photo by Rebecca Sumsion)

Though he has enjoyed a long and successful career teaching music, Tsugawa and others like him now see several barriers facing the arts in education (music, visual arts, theatre, etc.). There is a deep lack of diversity and arts programming in elementary schools, an area that Tsugawa says is largely overlooked but could make a huge difference in arts education in general. Some schools and programs do exist to help find solutions, but their reach is limited. There’s not a fix-all solution, but teachers, parents and students alike say they want to see additional support for arts education programs because of the beneficial takeaways and experiences such programs provide.

The Problems

Tsugawa teaches music education at BYU and serves as president-elect for the Western Division of the National Association for Music Education. The position gives him the chance to be up close and personal with some of the biggest problems facing the arts in education, including the inability to attract minorities.

“I believe that if 18 percent of your school is Hispanic, 18 percent of the kids in the music programs should be Hispanic,” Tsugawa said. “It’s not quite that. It’s quite heavy in the white Caucasian.”

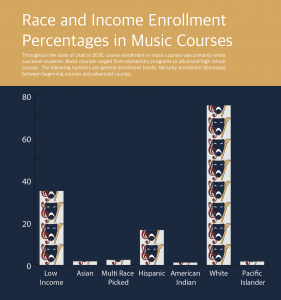

Tsugawa shared a 2016 report that showed a large drop off between racial minority enrollment in beginning and advanced music classes in Utah. For example, 2,146 Hispanics enrolled in a beginning choir class, “Chorus 1-Mixed” in 2016, about 14.9 percent of the total enrollment in chorus classes statewide. That percentage coincides with the percentage of Hispanic population in Utah, which is around 14 percent. But the enrollment for an advanced choir class, “Chorus III-Small Ensemble,” included only 100 Hispanics, or 3.7 percent of total enrollment.

“I have questions about whether or not we’re placing barriers in front of those kids,” Tsugawa said. “Maybe it’s because they don’t like that kind of music. Maybe it’s because we need to provide them with the kind of music they like.”

Diversifying repertoire is one possibility suggested and implemented by Tsugawa to attract more students, but Nicole Bright of Louisville, Kentucky, worries about the growing lack of appreciation for classical music. Bright worked several years with Fund for the Arts, an organization that provides arts experiences to students and other community members.

"Classical music..It’s a luxury that we cannot afford. I would say that it’s a luxury that we cannot afford to give away.”

“In places outside of the United States,” Bright said, ”classical music and classical voice are things that are heralded as great achievements, that are sought after. Here, in the United States, it became rich people goals. (For many taxpayers), ‘It’s a luxury that we cannot afford.’ I would say that it’s a luxury that we cannot afford to give away.”

Bright explained how the lack of classical music appreciation is mainly a problem of funding and giving kids the opportunity to be exposed to classical works and participate in the arts. Though there are ways to target underprivileged children, one demographic that Bright says are overlooked are “barely middle class,” families where parents have jobs but are just beginning their careers and don’t have extra funds.

“By the time the kids are in high school, parents are doing better, finally getting into upper level management,” Bright said. “But during those formative years for children — where parents are starting out in their career and can’t afford extracurricular activities — the parents are only making enough money so they don’t qualify for assistance in (providing) those art experiences.”

Enlarge

Rebecca Sumsion

Another problem that impacts the formative years for children is the lack of programs in elementary schools. “The state and district (levels) here in Utah don’t fund elementary music well at all,” Tsugawa said. “Let me just say for the record, it’s really bad. There are a handful of programs across the state where districts or schools see that it’s important and find money so that little kids can enjoy and learn about music. But that is not the standard across the state.”

In recent years, education systems have pushed to start rigorous, formal education at an earlier age. The push takes away crucial years where kids primarily learn by active exploration. The curriculum reform has worrisome consequences, according to articles from the New York Times and Wall Street Journal.

“Look at the way students learn up until age eight,” said Valerie Robinson, an elementary arts education teacher. “If children don’t explore before starting ‘skill and drill’ work, then they’re not going to be ready for ‘skill and drill.’ If they have exploration, then they’re ready and it’s a beautiful thing. We should teach based on how the brain works. When you look at Title I schools with struggling students, the school adds more math and science to boost scores. But if you give kids more life experience, then they’re better prepared to learn those subjects. Experience precedes understanding.”

Race and income enrollment percentages in music courses. (Infographic by Rebecca Sumsion)

Robinson has a lot of experience working intimately with art programs in elementary schools and has become an advocate for the importance of such programs and their impact on boosting overall education results. She earned a dual degree in music education and elementary education, equipping her with a specific set of skills to successfully integrate arts education into early childhood learning. She strives for integration because of the results.

Successful arts integration can precede improved academic performance. A 2013 study published by Mississippi State University concluded, “effective classroom arts integration can reduce or eliminate educational achievement gaps.” The study focused on eight public elementary schools and four private elementary schools that implemented arts education to foster retention and learning. Judith Philips, a research associate at MSU’s John C. Stennis Institute of Government and Community Development, generated the report. “The percentage of students scoring ‘proficient or above’ on standardized tests was significantly higher” for the schools that successfully implemented the arts initiative, she said.

Integrating arts into education has many benefits, but integration is easily misunderstood and overlooked. Early in Robinson’s career, she had to fight to show the value in music at school by demonstrating that music class was more than fun and games; it actually furthered classroom learning. Eventually, she gained the trust of teachers who then sought her help in creating curriculum to integrate music into other subjects. “Sometimes when people integrate music, they think singing a song about rocks is integrating,” Robinson said. “They may be using science as a tool, but if they’re not honoring the concepts within that, then they’re not really utilizing music.”

The Solutions

Some solutions to the problems facing the arts in education have been implemented on a small scale. They include Tsugawa’s experiments with different music choices to attract students of different minorities.

Other solutions come in the form of outside organizations that provide funding for programs that are not otherwise funded by the schools. The majority of funding for arts programs in schools comes from the state and independent organizations. These independent organizations seek to boost art experiences for schools without funding. They include Fund for the Arts in Louisville, Kentucky, and the Beverley Taylor Sorenson Arts Learning Program here in Utah.

Bright highlighted a program provided by Fund for the Arts called “5X5,” where every child from kindergarten to fifth grade receives one professional art experience a year. The organization is primarily responsible for Louisville’s professional organizations like the city ballet, orchestra and theater. “For a city our size to have all five major groups functioning in a city is unheard of. And it’s because of Fund for the Arts,” Bright said.

In Utah, the Beverley Taylor Sorenson Arts Learning Program helps target early education with initiatives like Art Works for Kids and other websites that contain curriculum guides. The program also provides funds to different schools to help boost arts integration. Robinson worked closely with the foundation for several years. “Beverley Taylor Sorenson was a fine arts advocate from a wealthy family who wanted children to have arts experiences in education with an integrative approach to core subjects,” Robinson said.

Enlarge

Rebecca Sumsion

The program puts arts specialists in elementary schools to “effectively increase student performance in every subject,” according to their website. The program has been introduced to 400 elementary schools (99 of which were Title I schools), 16 charter schools and 34 school districts serving over 300,000 students.

“The program also focuses on teaching integration and advocacy for arts education,” Robinson said. “It helps educate parents and the public as to why arts education is valuable and how it helps everything else in education.”

Julie Tate and her children were directly affected by the Beverly Taylor Sorenson arts partnership at their elementary school in Sandy. The school had a teacher who, for years, spent time after school running a choir and directing musicals. The programs didn’t feature many students because the funds were severely limited, but with the grant from the foundation, the program reached more students and put less stress on the teacher and on parent volunteers.

“It makes my kids’ lives more enjoyable,” Tate said. “I feel like we live in a world where there is such a push for linear progression, as far as academics and career aspirations go, which puts so much pressure on kids to decide what they want to be and set up a plan to be it.

"The arts gives them freedom to explore creativity, which is so desperately needed for kids."

“My son, who’s going into the arts for his career, would have never found theatre unless it was available to him early on.”

Tate has several children who have been involved in the arts, from painting and ceramics to choir and theatre. Whether they seriously pursued the arts or did it for an extracurricular credit, Tate saw the benefits.

Enlarge

Davis Fine Arts Blog

“I even have a son who’s a total athlete,” Tate said. “He’s very successful in sports and that’s what he loves. We forced him to be in an a cappella group one year. He has stage fright and he did not want to do it, but choir ended up being one of his favorite classes that year. I see how the arts enriched his life even though he didn’t feel he needed or wanted it. I believe it’s for everybody, even if it’s not their ‘thing.’”

While outside organizations provide funding, sometimes it is just the connections and network that can help boost arts programs. René Gutierrez, a high school choir teacher in the rural farming town of Delano, California, doesn’t feel there is a lack of funds for his program, primarily because of the low income nature of the community which qualifies them for more state assistance. The funds aren’t excessive, but Gutierrez finds success in networking with choir associations and nearby universities.

“As far as choirs go,” Gutierrez said, “we have access to a couple of pretty good networks of professional organizations for choirs. We’re part of that umbrella. If we want to go and sing at a festival supported by one organization or another, we have access to that. There’s a good network and we’re not really stuck. You can reach out and there are a lot of colleges and universities that host festivals.”

Why Continue with Arts Education?

It was the same each class period for the Sonous choir at Eagle High School in Boise, Idaho. Students slowly meandered to their spots and as the bell rang to indicate the start of class as the introduction to “Come and Find the Quiet Center” played on the piano. Repeatedly singing “clear the chaos and the clutter, clear our eyes, that we can see” sunk deep into the heart of Rebecca Soelberg.

Rebecca Soelberg sits in a vocal studio where she teaches voice lessons. (Photo by Rebecca Sumsion)

Soelberg thinks fondly of her time in high school choir. She is now a young and confident graduate from Utah State University where she studied vocal performance, a major she says she wouldn’t have chosen without her high school choir teachers.

“My teachers expressed a lot of confidence in my ability in small ways,” Soelberg said. “Their confidence in me helped me realize what I had to offer.”

Soelberg’s previous junior high and high school music programs were relatively small, so it was an exciting change when she moved to Eagle High School, which had a well-established choir program.

“Choir became an identity for me,” Soelberg said. “I blossomed and felt like I really could do something with music because there were so many people that were bonded by this musical experience even though they were so different outside of it.”

Carter Thompson, a freelance prop stylist in New York City, also found what course to pursue professionally because of his school’s art opportunities.

Thompson was involved in art from a very young age but was introduced to scenic design through theatre at his high school. He pursued scenic design as his college major, the only student to major in it while he was at BYU. That path led him to New York, where he found a niche specializing in prop design for photo shoots and events.

“From a young age I wanted to do something artistic,” Thompson said. “I always loved theatre, plays and going to shows as well as art, drawing and paints. Learning scenic design was a way to explore both of those things at the same time. If I had been presented an educational environment that didn’t include arts education, I don’t know how or when I would have found who I am now. I didn’t know I’d be here five years ago. All of that has come from being exposed to different things and discovering I liked them and was good at doing them.”

Interdisciplinary collaboration also affected Thompson’s education and his admiration for the arts. Thompson developed a love for storytelling throughout his middle school and high school English classes. But what really made the difference was having teachers that let him integrate his art ability into English projects.

“The thing that I liked the most was the storytelling aspect, being able to express ideas. I think I learned that more through language arts and literature. When I do illustration work, it’s usually based on text. The work I do with props or advertising always has a story to tell. It’s a matter of knowing or interpreting this verbal story into something that is a visual expression of that story.”

Madelyn Dial sight-reads new music during a BYU Singers rehearsal. (Photo by Rebecca Sumsion)

For Madelyn Dial, the arts provided a creative outlet and the opportunity to experience growth in an area outside of her other academic pursuits. While pursuing an accounting degree at BYU, Dial participated in BYU Singers, BYU’s premier vocal ensemble. Participating in the rigorous choir and getting good grades in the business school was no easy feat, but Dial managed it with strong time management skills, a trait she credited to music.

“Music taught me time management,” Dial said. “I had so many things I wanted to do, but music was a priority that I made a priority. Music taught me if you want it, you make it a priority. It also taught me how to stay focused for an hour at a time.”

Uniquely, Dial has experienced what is like to be a bridge between the arts and other educational subjects. Though sometimes she feels different from those she’s surrounded by, she strives to keep music in her life because of the benefits it provides.

“Whenever I go to my choir class, I say, ‘I’m so different from these people because all they care about is music, and I care about business,’” Dial said. ‘But then I go to my accounting classes and they say ‘there’s no room for beauty in this world, everything is money.’ I’m like this bridge. Music helps you see value in something that might not make you money, and that’s okay. When I was in junior core, I was in Singers and I was extremely busy. These accounting students would say, ‘why are you wasting your time on one credit that takes up 20 hours of your week?’ Because I need something beautiful. I can’t just live my life to make money. I have to make something else of value.”

"I can’t just live my life to make money. I have to make something else of value."

There are problems throughout arts education with diversity, funding and a lack of programs targeted to elementary schools. Though programs exist to help where they can, their reach is limited. But one thing remains clear — there will always be advocates for arts in education because they’ve benefited from their own experiences with the arts.

“I often wonder what impact or what difference it makes,” said Gutierrez. Teaching in the small rural farming town brought several limitations for Gutierrez and his students. But Gutierrez caught a glimpse of the legacy he left behind during another teacher’s retirement party. After coordinating a show choir for more than 20 years, the retiring teacher asked the choir to perform, which brought in several former students.

“That was kind of gratifying,” Gutierrez said. “A lot of them made the comment afterward, ‘this is your legacy, you have a whole generation of people up there.’ That was nice and that’s something that comes with time. It’s not something you see until you look back at it. I’ve had a lot of students come by and say the show choir was the funnest part of high school. For a lot of them, they become really happy memories and that’s all you have at the end of your life — good relationships and memories.”