Her hands won’t stay still.

They tug at loose strands on her jeans, wrap around the hem of her shirt, reach up to tuck her hair firmly behind her ear. She waves away the two family members who come to see what she’s up to and her slender fingers tangle together in her lap in an attempt to still themselves before fluttering back into motion.

It’s understandable, considering the situation. This will be the first time Helena Rhea, a 22-year old BYU student, has really talked about the past few years, outside of family and close friends, and it’s difficult to put into words.

Rhea has bipolar disorder. She was diagnosed after years of struggling through cyclic depression. Though Rhea is learning to handle the ups and downs of bipolar, the journey to the correct diagnosis and medicine was beyond words.

* * *

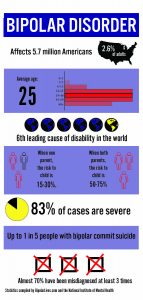

(Graphic by Jenna Crowther)

Bipolar is the sixth leading cause of disability in the world. According to the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, “nearly six million adult Americans are affected by bipolar disorder.” Bipolar generally affects young adults, but can also present in children and teenagers or adults and the elderly.

On average it takes three years to receive the correct diagnosis and medication, according to the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. For Jillian Lozanoff, a nurse practitioner at Jasmir Health in Lindon, Utah, the numbers are usually higher in her patients’ cases.

According to Lozanoff, 70 percent of bipolar patients are misdiagnosed before receiving the correct diagnosis, and 50 percent of patients with bipolar never receive the correct diagnosis at all.

Though bipolar disorder is fairly widespread, it is not easily diagnosed. However, bipolar’s high suicide rates and the negative effect the wrong medication can have on symptoms make it crucial to get the right diagnosis quickly and accurately.

* * *

An internet quiz helped Helena Rhea put a name to the emotions she was feeling. (Photo by Jenna Crowther)

It all began with an internet mental health quiz, the kind that shows up on a Facebook feed late at night. Rhea took it on a whim. Five minutes later, she had scored high on nearly every question. All she felt was relief. Here was a name and an explanation for the persistent feelings of sadness and anxiousness that had dogged her.

“Depression and anxiety,” it said. Rhea was relieved to have a name and to see there were medications and counseling that could help her. For the rest of her high school career and into her first year of college at BYU, Rhea rode the waves of her depression, changing antidepressants frequently as none seemed to cover that down feeling after a while.

“I was really functional in high school and my first year of college,” said Rhea. “Maybe I wasn’t feeling great, but I was getting things done and pulling good enough grades. I was frustrated because a lot of the time I was feeling like the meds weren’t helping, but it wasn’t ruining my life.”

Rhea and her high school cross country team pose for a post-race photo. Rhea decided she would serve a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when the age change announcement was made while she was racing. (Photo by Lauren Blair)

* * *

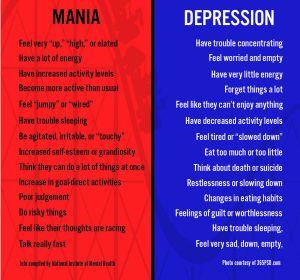

Bipolar disorder is characterized by cycling emotions and moods, generally between depressive lows and manic highs. During a depressive episode, a person might have very little energy, have trouble sleeping, feel worried or empty, or think about death or suicide.

A manic episode might present generally with a person feeling wired or jumpy, having a lot of energy, having racing thoughts, or doing risky things like spending a lot of money.

Each mood swing brings varying levels of energy and affects a person’s activity and ability to function in day to day life. Bipolar is generally split into two distinct types: Bipolar I and Bipolar II.

Bipolar I is characterized by manic episodes lasting at least seven days or requiring hospitalization, along with depressive episodes and mixed episodes. Bipolar II presents as depressive episodes followed by less severe hypomanic episodes. Various other types of bipolar disorder also exist that don’t meet the specific definitions of depressive or manic episodes.

The National Institute of Mental Health cautions health care providers that people generally seek help when they are feeling down, like during a depressive episode, rather than when they are experiencing mania. Bipolar is frequently mistaken for depression because of this. A careful medical history check is what they recommend as a way to distinguish between major depression and a bipolar depressive episode.

Lozanoff cautions that mania doesn’t necessarily present as days of nervous energy. She said that a manic period could be any emotion that is out of place for that person.

“During a manic or hypomanic episode, people stay up later. They get maybe two or three hours of sleep and get a lot done, and can feel on top of the world,” said Lozanoff. “They can enjoy it sometimes, because when your baseline is depression it’s nice to get things done. People don’t seek help during those times.”

Jillian Lozanoff works as a nurse practitioner at Jasmer Health in Lehi, Utah. She works to diagnose bipolar disorder in her patients as quickly and accurately as possible. (Photo by Jillian Lozanoff)

* * *

A major life event for Rhea was precipitated by a public announcement in the aftermath of a cross country race she and her teammates had just finished. Runners still trying to catch their breath crowded around cell phones, the same video streaming to each huddled group. There, sweaty and exhausted from an intense three-mile race, Rhea clutched her phone tightly and made her choice. The announcement said Latter-day Saint young women would be permitted to serve a two-year mission for their church at age 19 (they previously had to wait until age 21). She decided then and there that she was going to serve.

The desire to serve had always burned in her, and though she knew a mission would be difficult, she felt it wasn’t out of her reach.

After all, she was functional.

After getting clearance from her psychiatrist, who gave her antidepressants to help her through her depression, Rhea submitted paperwork for her mission. She had taken the medications before, but nothing seemed to stick.

“I took antidepressants through high school and my first year at BYU,” said Rhea. “It seemed like the meds would help my symptoms for a few months and then I would start to go downhill again.”

Then her mission call arrived in the mail. New clothes were packed into new suitcases. Tears were shed on the curb, but Rhea felt ready as her family pulled away from the Missionary Training Center, leaving her to begin her proselyting mission. She had antidepressants and the desire to make her mission work, despite her challenges. That determination had always been enough to help her achieve her goals.

* * *

An adverse reaction to medication can be an indicator of bipolar disorder, according to Lozanoff. When a patient comes to her seeking help, she looks for certain key markers that can indicate a bipolar disorder rather than generalized depression.

“If they come in saying they’ve been on five different antidepressants and that nothing has ever worked, or that they worked for a bit and then stopped, then it stands out,” said Lozanoff. “Or if they don’t respond to antidepressants in the way they should, like they started taking them and felt more anxious and depressed. If it’s an adverse reaction to antidepressants, then I’m thinking about bipolar.”

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, antidepressants can cause rapid cycling and manic states in people with bipolar disorder. Getting on the right medication as quickly as possible is crucial when dealing with mental health. The wrong medication can have disastrous effects on someone’s life, as in the case of Michaela Riley, a 24-year-old Provo resident.

Riley did not have bipolar disorder. Her mother did though, and that combined with her own racing thoughts and depressive episodes — common bipolar symptoms — convinced her psychologist that she must be bipolar. She was prescribed strong antipsychotic medication from the start.

The following weeks were like nothing Riley had ever experienced. Her symptoms were thrown into overdrive by the medications that she jumped between for months. She felt like her skin was on fire. She couldn’t sit still, couldn’t think. She lost longtime friendships and failed her classes.

In reality, Riley had Attention Deficit Disorder and didn’t need to be on such strong medications. She lost two months to a misdiagnosis that generalized her symptoms and ignored her unique medical history.

“At the time, I trusted my doctors. I thought they knew best,” said Riley. “They really couldn’t have messed it up more for me than they did…There should be a more skillful way to go about it.”

* * *

The days that immediately followed Rhea’s return home from her mission were a blur.

Terrible eating habits had left her weak and thinner than normal, and no amount of sleep could cut through the haze of exhaustion that surrounded her. She battled thoughts of death and suicide that had followed her onto the plane from Germany back to Utah.

“It was really wretched,” said Rhea. “I definitely didn’t want to leave my house for the first few days, which turned into the first few months.”

Finally she realized she needed more help. After years of functionality, her moods were overwhelming her, and she felt like her career, her relationships, and her future were suddenly on the line.

“I just felt for the first time that ‘there are things that I can’t achieve because of this,’” she said. “I’d never felt like that before, like I was inhibited. I’d been able to push my depression and anxiety to the back burner before, and it wasn’t something that people would ever notice. But then I felt inhibited and like everybody knew.”

* * *

Madeline Burton often goes on walks in the mountains when she feels out of control. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at age 19. (Photo by Jenna Crowther)

Undiagnosed bipolar disorder comes with the high risk of poor outcomes, according to Lozanoff. Getting the right diagnosis saves lives.

According to Dr. Wes Burgess in his book, “The Bipolar Handbook: Real-Life Questions with Up-to-Date Answers,” people with bipolar disorder are more likely to attempt suicide.

“Thirty percent of individuals with bipolar disorder will attempt suicide during their lives, and 20 percent will succeed….Suicide is more common in bipolar depression than in unipolar major depression, panic disorder or even schizophrenia.”

Madeline Burton, a 22-year old UVU student, noticed something was wrong way back in high school. Over the years, she was mostly depressed, but would sometimes feel like she was coming out of it before crashing back down. Her moments of happiness felt fake and she felt out of control. She said that she was suicidal for a while.

“I thought about death a lot,” said Burton. “But what kept me going was the ‘what ifs.’ What if it does get better? Don’t I want to stick around for that?”

Burton was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at 19.

* * *

For almost a year after her mission, Rhea went through periods where she wasn’t sure doctors would ever figure out how to help her. She took time off from school and stopped working, devoting all her time to searching for answers and help.

She found her way to a therapist and psychiatrist and tried out more medications. When her psychiatrist mentioned bipolar as an option, she wasn’t happy with the idea.

“I was honestly kind of angry with my doctor,” said Rhea. “I didn’t want to believe it because it sounded so serious and scary to me.”

Rhea didn’t know much about bipolar, only mentions of the psychosis and mood swings she had seen on TV. She didn’t want that stigma to be associated with her.

However, Rhea grew to accept her diagnosis and found medication that was a good fit.

“A while after receiving a diagnosis I did feel really grateful for the clarity and direction it afforded,” said Rhea. “It helped me make sense of my emotions and set me on a better medication course.”

* * *

Alyssa Felt (left) and her sister, McKenzie, live together in a basement apartment of their family home. Watching a family member be hospitalized was their first real experience with bipolar disorder. (Photo by Jenna Crowther)

For 22-year-old BYU student McKenzie Felt, her first interaction with bipolar was when a family member began suffering through intense mood swings. She ended up being hospitalized and receiving a bipolar diagnosis.

Felt only knew what she’d learned from watching television, and the media tends to exaggerate bipolar symptoms, she said. As a result, she didn’t know how to react or how to talk to her relative during that time.

“When you see examples, it usually is hyperbole,” said Felt. “That’s all I’d seen and all I knew was that there were drastic changes in emotion.”

Lozanoff said that better education for health care providers and the general public about bipolar disorder is necessary to help get the right diagnosis quickly.

“I am really frustrated by the lack of provider training where bipolar is concerned,” said Lozanoff. “When people come in with mania, with depression, and they leave undiagnosed, it can be really discouraging. We want people to get help and that means we need to get better training to recognize bipolar.”

Recognizing the symptoms and patterns of bipolar are critical to getting the right help. Burgess’ book shows the risk of suicide drops dramatically when patients receive adequate treatment. Medications like the mood stabilizer Lithium have been reported to have a success rate as high as 85 percent, according to the Surgeon General Report for Mental Health.

“Bipolar is credibly treatable,” said Lozanoff. “People will come in who have been depressed for 20 years, who have been hospitalized multiple times. When we get them stable and on good medication, they will come back saying they are feeling better than they ever have. There is hope and there is good medication that can help.”

(Graphic by Jenna Crowther)