April 27, 2017

Mary Serawop says she remembers every detail about returning to prison after leaving her newborn twins- only three days old- behind at the hospital. “It was so surreal. I remember the sound of the doors slamming behind my back and thinking that I didn’t know when I would ever see them again.”

Mary was serving a two-year sentence at the Utah State Prison. When she was booked in 2013, she had only recently discovered she was pregnant, and would spend the remainder of the pregnancy incarcerated. Mary’s pregnancy had been considered “high risk” and she was placed on bedrest. She spent 4 months in the hospital, but after receiving a cerclage, a procedure to close the cervix to help prevent early childbirth, she was told that the hospital stay was too expensive, and she would need to return to the prison infirmary until it was time for her to deliver.

"At any minute I could have given birth, and I didn't want to do it there." Mary Serawop

“The infirmary is basically just a hole in the corner of the prison where they stick you in and hope you will get better. It was hard,” Mary recalls. “I didn’t have contact with anybody for the entire time I was there. I was depressed and I was alone.” Not only was she alone, but she was afraid of welcoming her two baby girls into the world in such a dark place. “At any minute I could have given birth, and I didn’t want to do it in there.”

According to the American Journal of Public Health, between 6 and 10 percent of incarcerated women are pregnant. Annually this amounts to around 9,500 expectant mothers behind bars. These women often receive minimal amounts of prenatal care and little to no attention during postpartum recovery. This medical neglect can often affect the baby and mother, physically, mentally and emotionally without treatment available.

According to medical specialists, they are doing their best to accommodate the incarcerated mothers, but some say there is nothing else they can do to make the situation more pleasant.

Prenatal Care

Spencer Tong is a Utah County Jail Correctional nurse. During his three years working there, he has had a lot of experience dealing with the overall care of both the fetus and the mother. According to Tong, when someone of childrearing age is admitted to jail, they are immediately given a pregnancy and drug test. Tong says that only about half the pregnant women admitted are aware of their pregnancy.

(shot and edited by McKenna Flores and Jaylen Bohman)

Tong states that while he has empathy for pregnant women in prison since seeing his wife pregnant, he believes the care is adequate, even if it is more uncomfortable behind bars. Still, there are several specific women’s health problems in prisons.

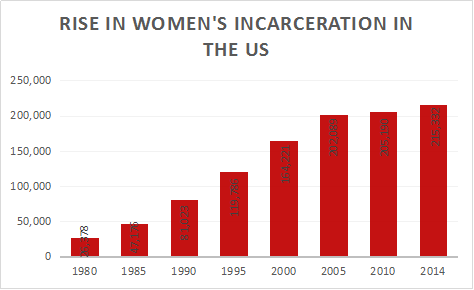

The number of women arrested has increased dramatically nationwide over that past 20 years. According to the National Women’s Law Center, the number of women in prison is larger than it has ever been, with the amount of women incarcerated for drug crimes now surpassing that of men.

(Image by McKenna Flores)

Much of the prison system and policies have been structured for men, ignoring the reality of female inmates. This oversight has caused neglect in women’s care generally, and specifically prenatal care. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that only about 54 percent of incarcerated pregnant women receive prenatal care, and that care varies widely from state to state.

Labor and Delivery

Currently in Utah, there are no anti-shackling laws, meaning a woman could go through pregnancy, labor and delivery cuffed and shackled to the bed.

The American Civil Liberties Union reports that, “Restraining pregnant prisoners at any time increases their potential for physical harm from an accidental trip or fall.” This type of accident could affect the fetus as well. The need to move freely during labor, delivery, and post-delivery is restricted by shackling. The same source said that, “National correctional and medical associations oppose (shackling),” yet the practice continues in most states.

(Video shot and edited by Jaylen Bohman)

During labor and recovery, Utah also doesn’t have strong privacy protection laws. Amnesty International recommends that female prisoners be guarded by female corrections officers whenever possible, but for Mary that wasn’t the case. She said she was never left alone during labor or the three-day recovery period and was always watched by a guard; only one was female.

“The guards weren’t very sympathetic,” she said. “I remember one night, one of the twins wouldn’t stop crying and the guard was getting so angry, and he kept asking me to quiet the baby down.”

Post-Partum

Utah’s policy is that after giving birth, inmates get three days with their infants before returning to prison. For Mary, after her three days she was quickly separated from her new babies and was returned to prison and placed in what is called R&O. “For three or four days I was left alone there on lockdown for 23 hours a day. I had no contact with anyone.”

According to the Utah State Prison website, R&O stands for Receiving & Orientation, “where new offenders being admitted to the prison go through initial assessments.” The site continues to explain that while being held there “inmates take a test… (to) evaluate risk factors, appropriate level of supervision, and other useful information.”

Mary was unsure of why it was necessary for her to be in R&O so long, since she had only been out of the prison for a couple of days, and feels that the time she spent there proved to be some of the most difficult days of her life.

“If I was out in the population with everyone I think I would have been able to cope better with it all, but during those couple of days there was nothing else to do.”

"I was alone and the only thing I could do was cry. I cried, and I slept.” Mary Serawop

Mary isn’t the only inmate with this type of experience. Amy Husband was booked into the same jail around her third month of pregnancy, and at the time didn’t know how long she would be there. “When I was finally told my release date, I couldn’t believe it.” Amy was sentenced to two years meaning she, too, would be giving birth while behind bars.

Amy also suffered with feelings of distress after being separated from her son.

“I felt alone. All I wanted was to talk to somebody and have somebody to listen. But I didn’t have anywhere to turn.” These two women said they were likely dealing with post-partum depression (PPD), which isn’t uncommon.

According to the American Psychological Association, up to 1 in 7 women experience PPD shortly after giving birth. They say the risk for PPD increases if the new mother is “…experiencing particular stressful life events in addition to the pregnancy, or if they don’t have the support of family and friends.” Most prisons don’t allow any extra contact from the women’s support system after delivery. This, along with the added stress of imprisonment could explain why so many incarcerated women experience PPD.

(Picture Shot by McKenna Flores, edited by Jaylen Bohman)

Unfortunately, due to the prison’s overloaded mental health care branch, it is extremely difficult for women to find the help they need. In order to see a mental health professional, an inmate has to put in a request, and then is put on a long waiting list until counselors have an opening. Women with post-partum depression aren’t given any special treatment within the prison system. They have to wait at the back of the line just like everyone else. This isn’t the only lack of post-partum care. Both women say they dealt with extreme pains of post-labor with next to no help.

“The care was even worse after the babies were born. My milk came in after 3 days and they wouldn’t give me anything to wrap my breasts. I couldn’t pump. There was nothing to make the pain go away. I didn’t get Ibuprofen until close to 7 days after getting back from the hospital.” Mary said. She recalls feeling so desperate to release the pressure in her breasts that, despite being told not to at the hospital, she would often squeeze them.

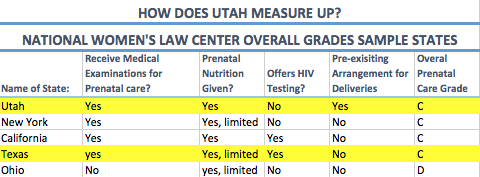

Dr. Corianne Sweat, an OBGYN, worked at the Texas Correctional Department while she was a resident at UTMB-Galveston. While there, she worked often with expecting inmates, and says that the standards in place are really to help assure safety for everyone involved. Texas and Utah prison medical standards are very similar, both receiving a “C” grade for overall care according to the National Women’s Law Center.

(Picture shot and edited by Jaylen Bohman)

“The whole process is to make sure we have the best outcome for the mother and the baby,” Says Dr. Sweat. She understands the complications of giving birth behind bars but believes the care is as good as it can be considering the circumstances.

(Video shot and edited by McKenna Flores)

Custody Issues

After her delivery, and three short days with him, it was time for Amy to say goodbye to her son.

“When they gave me my release papers, and told me it was time to go, they wheeled my baby out of the room and it broke my heart not knowing when I would see him again,” Amy said.

The boy’s father came that day to collect their son, and Amy hoped that he would care for him for the next two years, and when she was released she would join the parenting process as well. What Amy didn’t know was that, aside from a couple of visits, after prison, she never would see her son again.

When she was released her son was 2 years old and Amy says he had no idea who she was, and would act “skittish” when she was around. After telling the boy’s father she was not interested in pursuing a relationship with him, he disappeared with their son. Shortly after this time, Amy broke parole and needed to serve 8 more months. It wasn’t until being released that she found out her son’s father had been arrested for child sex crimes. Mortified, Amy immediately went to the courts to try and get custody of her son, only to find that relatives of the father had custody. The commissioner who heard her case told her that it would be impossible for him to award her custody after such a long period of time because it would be “too traumatic for the little boy, who didn’t even know her.”

Her son is now 9 years old. She has tried contacting the family he is with to establish some sort of connection with her son that she never knew, but has been rejected.

“I have tried everything I can think of at this point.” Amy said, “Sooner or later I think he is going to look at the people that are raising him, and then look at himself in the mirror, and hopefully he will say, ‘I don’t look like these people,’ then maybe he’ll reach out or try to find me. I can only hope that happens sooner rather than later.”

Mary also struggled to form a relationship with her girls. Her step-family picked them up and has had custody ever since, but unlike Amy, Mary received visits from her twins while in prison.

“They came and saw me a lot, but I was scared of the contact. It was hard to hear them cry and not be the one to understand what they needed. I couldn’t help them.”

Continuing Problem

The future of women giving birth in prison is still uncertain. While having a child behind bars may will never be the ideal delivery scenario, there may be better ways to work through the mental and physical hardships that accompany this experience. Different solutions have been implemented nationwide such as prison nurseries, a system that allows new mothers to keep and raise their children from within prison walls.

Most mothers come from backgrounds of domestic violence or substance abuse, and according to the National Women’s Law Center the majority of women coming out of prison will fall back into the same cycles of abuse. Many of the incarcerated women are repeat prisoners, and according to correctional nurse Spencer Tong, over half the women don’t even know that they are pregnant.

A program like prison nurseries, according to the National Women’s Law Center, promotes bonding and healthy family relationships between the parent and the child. This not only gives an opportunity to bond with the child, but decreases the chances of postpartum depression.

Other potential programs could include the ability to pump milk for mothers who have babies in close proximity or for those serving short terms that wish to breastfeed after leaving prison. More psychological care could be given to those mothers who seek help, and parenting classes are an option to give those babies and mothers the best chance at a positive family unit for futures to come.