An army veteran who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan. A student who dreams of creating her own business. A town councilwoman in Alberta, Canada. An owner of a nonprofit organization. A Venezuelan immigrant in the middle of a divorce.

Despite their diverse backgrounds and situations, these women have a few things in common. They are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They are mothers. They each have a mental illness.

And they all have a story to tell.

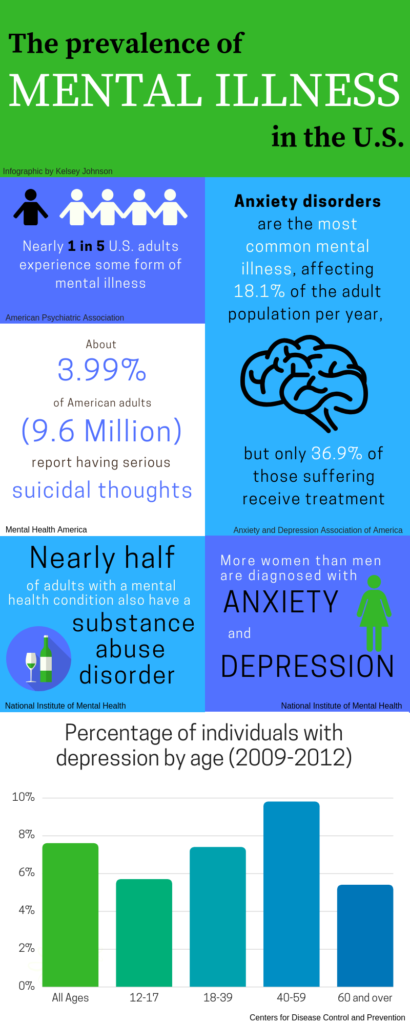

According to the American Psychiatric Association, 19 percent of U.S. adults currently experience some form of mental illness, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website reveals that more than 50 percent of U.S. adults will be diagnosed with a mental illness or disorder at some point in their life.

Data shows that about 12.8 million parents (18.2 percent) have a mental illness, with mental illness more common among mothers than fathers. According to a 2011 article from the ISRN Nursing Journal, women with a serious mental illness are just as likely to parent as other adult women in the general population, and one third of female mental health services users are parents with dependent children.

Mothers are in a unique position; not only do they experience hormonal shifts and other physical adjustments during pregnancy and childbirth, but they are the predominant caretakers of children in the United States. According to a 2016 report from the Pew Research Center, moms spend 14 more hours a week on child care and housework than dads do, and 78 percent of all stay-at-home parents are mothers.

Mothers are in a unique position; not only do they experience hormonal shifts and other physical adjustments during pregnancy and childbirth, but they are the predominant caretakers of children in the United States. According to a 2016 report from the Pew Research Center, moms spend 14 more hours a week on child care and housework than dads do, and 78 percent of all stay-at-home parents are mothers.

Brigham Young University assistant professor of psychology Melissa Jones has been a therapist for about 15 years and said motherhood can exacerbate the symptoms of mental illness.

“A lot of managing a mental illness requires good self care,” Jones said. “And when you’re the mother of newborn, that self care kind of goes out the window. It’s hard to get enough sleep. It’s hard to exercise and feed yourself well.”

Mothers and mental illness is not an uncommon combination, touching the lives of not only those individuals but their family members and loved ones as well. Five women, each with a different mental illness, recently shared what it is like to be a mother dealing with mental illness.

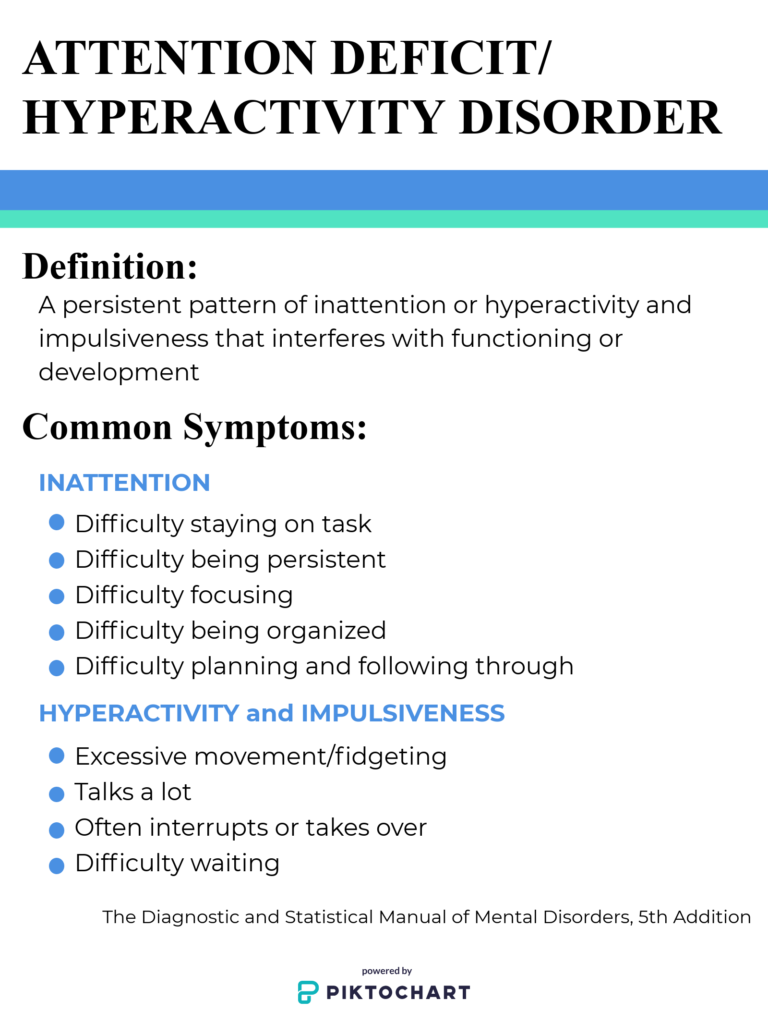

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Graphic by Kelsey Johnson

Provo resident Jill Osborne, 30, identifies as a “5-year-old at heart,” darting around an apartment bustling with piles of laundry, plates of food, and toys belonging to her 5- and 3-year-old sons. She sits on the ground cross legged, her long blond hair in a low ponytail, and interrupts her own train of thought to ask if she can paint her nails while she talks. She leaps up and grabs her supplies, bringing an armful over to a low table, and promptly begins speaking about a different topic entirely.

Osborne was diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in May 2018. Despite struggling with it her entire life, Osborne said until she received medication, she “had no idea that you didn’t have to live in that much turmoil in your head.”

“It’s like all these thoughts are in a funnel,” Osborne said when describing her ADHD. “And you don’t really have great decision making ability, and you don’t know which [thoughts] should come out of your mouth.”

Osborne divorced her husband in 2015 and, after leaving a job, she ended up in a situation where she was either sleeping in her car or on the couches of friends while her children stayed with their dad. Osborne said ADHD heightened her fear and made everything exaggerated, living in constant panic of losing her children to the point that it was impossible for her to focus and go through the necessary requirements to apply for jobs.

In the end, she was able to get help and medication, allowing her to get an apartment and job and to become a student at Utah State University studying speech pathology.

Enlarge

Lucia Smith

However, ADHD is still a part of Osborne’s everyday life. While she believes all mothers have an innate awareness of everything around them that might affect their kids, Osborne said she has so many thoughts that she has a hard time discerning what the most important thing would be, and she has a hard time keeping track of time and often runs late.

Osborne said when it comes to short-term memory, she’s in the lower 18th percentile for the general population because her thoughts come so quickly that they become fleeting. In order to accommodate, she said she’s had to learn to let go and trust that God will help things to be taken care of. She also keeps a task list on her phone and writes down whatever she can on sticky notes.

While ADHD has made her life challenging, Osborne said when it comes to coping as a single mom, she doesn’t know how she would do it without ADHD.

“I would rather, because of ADHD, have a challenge than have a normal [situation] — I kind of do better with a little bit more intensity because it keeps me on my toes,” Osborne said.

Osborne said motherhood is “the worst and best challenge in the world” due to its unrelenting nature, and she said it can be even more difficult when women see their only identity as being a mom. When women view themselves this way, she said, and a child makes bad choices, it’s not only hurtful but crushing to them. Osborne said she’s come to learn that she’s a daughter of God first, an individual person second, and a mom third.

“You are not a failure. You are just going through what is called parenthood and it sucks. And you’re not good at it, but who is?” Osborne said. “So you know what, you can be a daughter of God first, you can be you first, and that is not selfish. That is healthy. And the more healthy you are in that part of your identity, then the easier it becomes to be the kind of mom who truly delights in her children.”

Enlarge

Lucia Smith

As for Osborne’s life now, she takes medication and she’s learned how to be aware of her strengths and weaknesses when accomplishing tasks and how to embrace the person she is, ADHD and all.

“I’ve been able to draw on that part of me, that might never grow up,” Osborne said. “And maybe it’s okay if it doesn’t.”

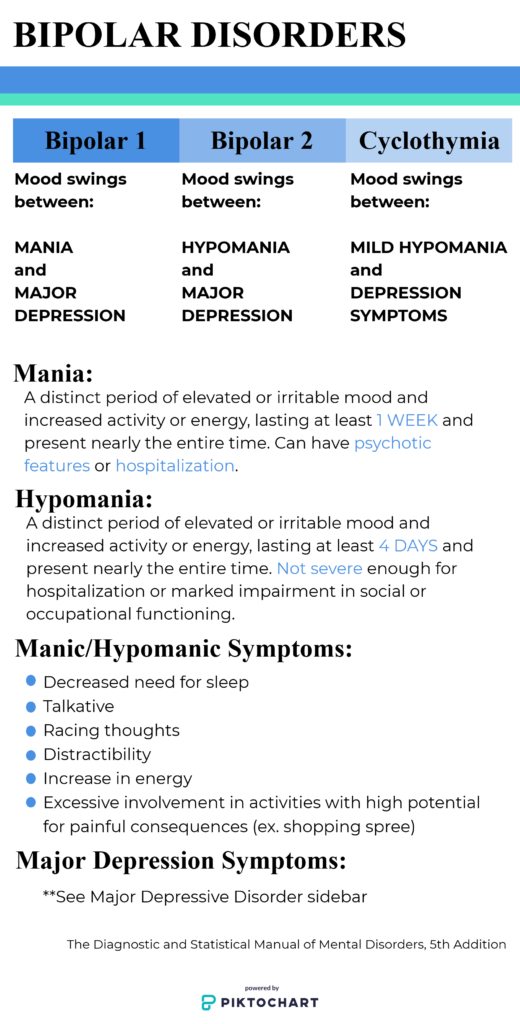

Bipolar Disorder

Graphic by Kelsey Johnson

Natasha, 30, is not weak.

After six years in the army fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, she’s now a stay-at-home mom in Kaysville with two daughters under the age of 6. Despite her husband’s frequent absences as he continues to serve in the military, she spends her time exploring new places with her kids while also taking online classes to fulfill her dream of becoming a nurse.

On top of it all, Natasha has also been diagnosed with PTSD and a Bipolar 2 disorder. Bipolar 2 is a milder form of Bipolar 1, with hypomanic episodes rather than full manic episodes. These episodes are accompanied by bouts of depression, resulting in dramatic mood swings in everyday life that can be hard to predict.

Natasha, whose last name has been withheld due to the nature of her husband’s career, said her hypomanic periods used to last up to three weeks before being on the right medication; now they last about a week. During her hypomania, she said she’s flooded with energy to the point where she “can’t stop moving or thinking” and becomes “hyperfocused” on projects or tasks.

“It feels nice for a while,” Natasha said. “I can get an insane amount of stuff done, like I tore up my whole bathroom in a day by myself. I have a whole bunch of energy.”

However, with the influx of energy comes some negative side effects. Natasha said her paranoia, which is tied to her PTSD, tends to spike during this time. She also had problems with excessive shopping to the point where she’d get to a store and not even remember how she got there in the first place. Despite increased productivity, Natasha says she becomes much more short-tempered with her kids because they can get in the way of what she is hyperfocused on.

“I went on meds initially because I was yelling so much at the kids,” Natasha said. “I felt like I was traumatizing them and they would become psychopaths like me.”

Natasha also experienced bouts of depression, including postpartum depression with each of her daughter’s births. Natasha said she felt ashamed of how difficult having her first child was and, because of this, didn’t reach out to anyone.

“In my head it was like, ‘Everybody does this, I have to be able to do this. I have one baby, people have six, right?’ But I couldn’t handle it,” Natasha said.

Natasha said she never enjoyed the full dependence babies had on her and still doesn’t like holding babies because of anxiety about dropping them. The cry of a baby is also triggering, she said, and sometimes it became so difficult that she would lock her baby in a bouncy chair and climb in the shower “just to drown the noise out.”

However, as her children grew older, Natasha still continued to struggle. Natasha’s husband was often gone, and Natasha said because of her mental illnesses, she felt more susceptible to stress and irritation, which then led to her yelling at her kids and then later feeling immense guilt. Ultimately, she said, it was the guilt she felt from being a “terrible mom” that first led to her to try antidepressants. The pills ended up making her feel worse, a common effect for those with Bipolar. Ultimately, she was correctly diagnosed and given medication that she now takes on a daily basis.

Natasha also has a trained service dog that she says helps her predict when she’s beginning a stage of mania, allowing her to be more aware of herself during those times so she can regulate herself better. She’s also realized how sleep affects her, saying that too little sleep triggers hypomania and too much sleep triggers depression, so she takes medication in order to regulate the amount of sleep she gets.

Although Natasha can’t control that she has a mental illnesses, she said when she yells at her kids, she always tries to sit down with them later and explain that it’s her problem and not their fault. She said she is very open with her daughters about it because if either of them ever have issues as well, she wants them to feel that they can talk about it too.

However, for Natasha, the most difficult relationship through this all has been with her husband. Because of his career in the army, Natasha said her husband was often gone during some of her hardest times and had a difficult time believing she had mental illnesses and struggled to understand her. Natasha said her husband had never had experience with mental illness before marrying her and was hesitant about Natasha taking medication because he saw it as a “band-aid.” His reaction caused Natasha to feel even more guilt when she made the decision to start.

While Natasha’s husband has grown to accept and understand her mental illnesses, she said she’d give the advice to all spouses of those with mental illness to not judge. When someone is having a hard day, she said, one of the worst things another person can do to them is to point out the things that person did wrong.

“The best thing you can do is listen to someone without judgement and tell them that you love them. Or bring them a freaking box of cupcakes,” Natasha said.

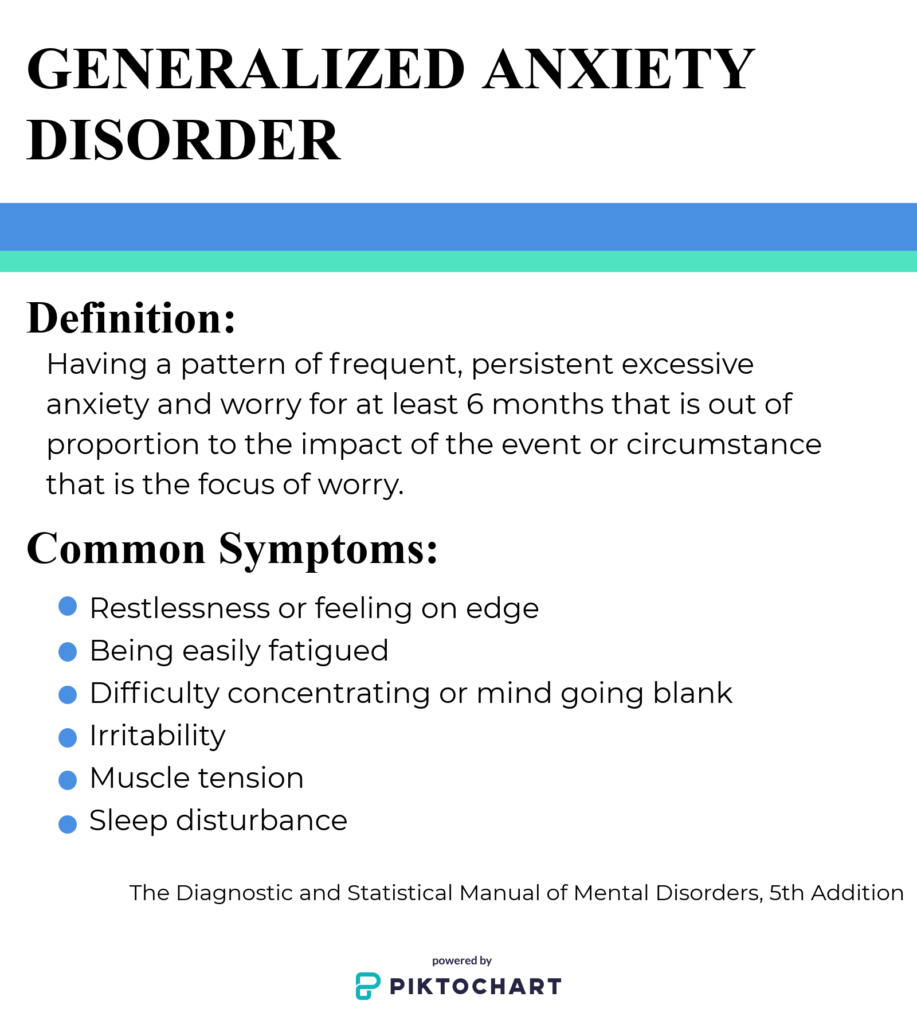

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Graphic by Kelsey Johnson

Every morning Betzabeth Rivero, 34, makes a list of what is real. She writes out the day’s schedule, as well as characteristics about herself. However, what’s most important is what she does not write down – her fears for the future.

“It’s really hard work because I have to do it every single day. I wake up and I say okay, this is the plan for this day and this is what I know will happen today and try to focus on the moment,” said Rivero, who lives in Provo.

Lists are one of the many ways Rivero copes with general anxiety disorder, something she has struggled with for seven years, starting when she lived in Venezuela.

When it comes to Rivero’s life, there are plenty of challenges to feel anxious about. Rivero began a divorce from her husband while living in Venezuela and moved to the United States in 2017 with her now 9-year-old daughter. Rivero attends BYU’s English Learning Center and works as a custodian for the university’s Helaman Halls dormitories. On top of her duties, Rivero also has arthritis and fibromyalgia.

However, generalized anxiety disorder is more than concern about life’s daily challenges. According to the most recent edition of “The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” generalized anxiety disorder “is characterized by a pattern of frequent, persistent excessive anxiety and worry that is out of proportion to the impact of the event or circumstance that is the focus of the worry” and must cause significant distress or impairment.

“Anxiety is when you’re afraid of something that might happen,” Riverso said. “So sometimes it’s really hard to manage that and be balanced, especially when you have a kid because you need to be completely capable of taking care of her. So sometimes I just tell myself, ‘I’m okay, I’m okay’ and after she goes to sleep, I just cry.”

Enlarge

Kelsey Johnson

Rivero likened her anxiety to the feeling of being compressed from all sides and said she accommodates it through prayer, meditation and breathing exercises, all of which help her to focus on the moment rather than her fears for the future.

Because of her physical ailments, Rivero said she has a difficult time not comparing herself negatively to other people in her classes, especially when it comes to grades. She said she’s had to learn how to accept that she’s not at the same level as everyone else by being aware of her differing circumstances.

“You are not the same as these other people,” Rivero said, referring to what she tells herself. “But you have a daughter, you work, you study, you have a house and they are single and don’t have children, so if they go a little ahead of you, that’s okay.”

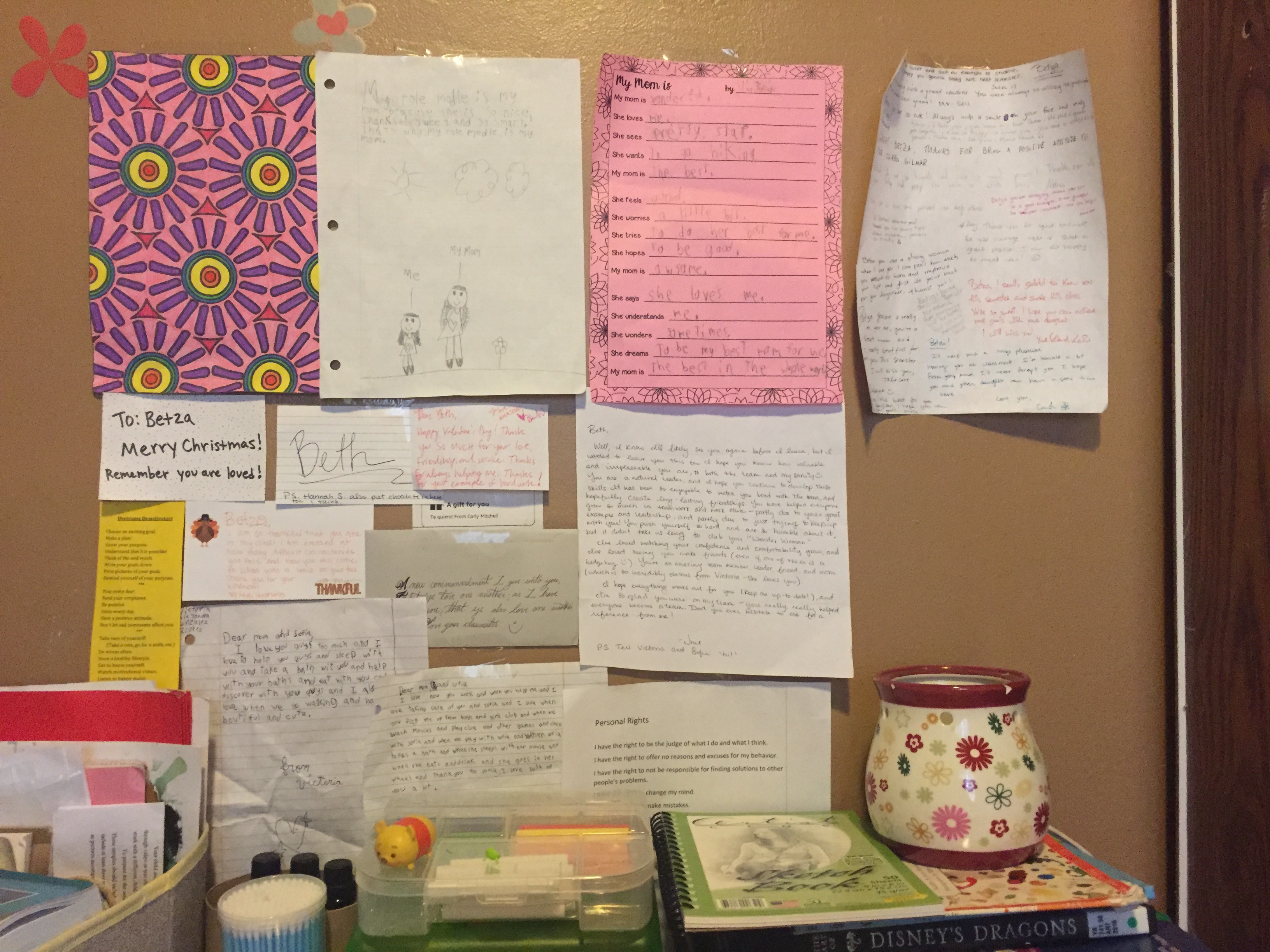

Along with her anxiety, Rivero also experiences major depressive disorder, a common combination for individuals with mental illness. In order to accommodate her mental illnesses, Rivero said she attends counseling and keeps a wall of quotes in her bedroom where she tapes kind messages to herself as a daily reminder that she is enough.

Enlarge

Kelsey Johnson

Rivero also tries to be as transparent with her daughter as she can, saying that in her birth family she saw that if things are kept hidden, they eventually pop out and it can look like it was a lie. Since Rivero worries about the impact her mental illnesses may have on her daughter, she has conversations with her daughter about topics such as responsibility versus fault, and tells her when she’s having a harder day.

“It’s a way that she can understand me and I can feel like I’m honest with her and we can work together because we are a small family, we are just two,” Rivero said.

Enlarge

Kelsey Johnson

Rivero said her mental illnesses have taught her to be more grateful because of the necessity of looking “on the bright side of things.” She said she is also learning how to acknowledge her limits.

“I’m just trying to know and to recognize when it’s healthy for me to keep pushing in order to not be lazy and when I’m pushing too much,” Rivero said. “It’s a process to [get to] know yourself.”

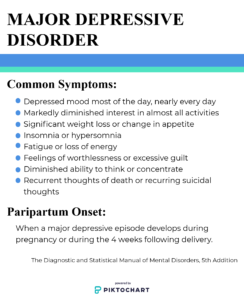

Major Depressive Disorder

Graphic by Kelsey Johnson

Kristi Edwards, 38, was a stay-at-home mom of two boys when she started to seriously consider committing suicide.

Edwards had experienced bouts of depression before, saying she first noticed it during her parent’s divorce in junior high, but it wasn’t until the move back to her hometown of Fort Macleod, Alberta, Canada that it came to a head.

Shortly after her arrival in a new ward, Edwards was asked to teach the young women, a calling that left her feeling isolated from the other women her age and pressure to be an example to the youth that she felt she failed to be. Edward’s husband worked full time as well as attending full-time school, severely limiting the time she had with him.

The birth of Edward’s second son only exacerbated the symptoms. While she loved her baby, Edwards said she didn’t bond or connect with him in the same way she had with her first son. She felt she was “missing the mark” as a mom and was sure that if she were to take her own life, her husband would finally be able to find a better wife and mom for her children.

“I was more willing to let the baby play on the floor or in his crib than to cuddle or snuggle or hold the baby all the time,” Edwards said. “More often than not, I would just turn cartoons on the TV and my older son would be running around like a crazy person and getting into everything but I just didn’t have the energy or desire to do anything about that, so I would just sit on the couch and be a lump and then he would run around.”

Edwards said since Fort Macleod was her hometown, she felt pressure to be the “happy, exuberant, friendly and helpful” person that she had been for most of her life. She said this led her to pretend to be happy even though, on the inside, her depression only continued to mount.

Enlarge

McClung Photography

Edwards said she got to the point where suicide became a “very common thought” for her. She Googled methods on the Internet, but said she stopped herself from an actual attempt due to the worry about “who would have to clean it up.”

Edwards realized she needed to get help the day her sons dumped brown sugar all over the kitchen. Sticky and grainy, the sugar was worse than the day before when they had showered rice all over the floor. Feeling herself being pushed over some kind of “edge,” Edwards said she stuck her boys in the bathtub and called her mom, bawling until her mother arrived and then going straight to her room.

In the days that followed, Edwards met with her doctor, got started on medication and received a referral to a psychiatrist and therapist. She said she was diagnosed with postpartum depression and a major depressive disorder, something that filled her with shame.

“I was really worried about being the let down or the person who dropped the ball as far as abilities and what I could accomplish in life. I didn’t want to be sick or unable to function or a drain on society,” Edwards said. “…I didn’t want people to think that I was a failure and that I wasn’t good enough to fix myself.”

Despite her initial reproach, Edwards started counseling and taking medication. When her youngest son was 6 months old, she started a part-time job in an office full of bright light and people who became good friends, a stark contrast to how she would have described her life up to that point.

“When I got married and then had kids, it’s like your world shrinks. You’re in a box. And that box is very dark and small and compresses you until you can’t take it anymore and you think you’re better off to just let it all go because you don’t want to live in that box anymore,” Edwards said.

Enlarge

Kristi Edwards

Edwards said she’s an extrovert, causing her to have an extremely difficult time as a stay-at-home mom getting the interaction that she needed. However, since being diagnosed, she has been able to find ways to give herself all that she needs in order to take care of herself. Now Edwards is on town council, giving her the intellectual and social elements that she needs in order to practice good mental health. She also has learned how to accept her mental illness for what is.

“The one thing I have done is give myself permission to have ‘off days’, to send my kids to school in the morning and then curl up in my bed and sleep until it’s time to go pick them up at the end of the day. And that’s okay,” Edwards said.

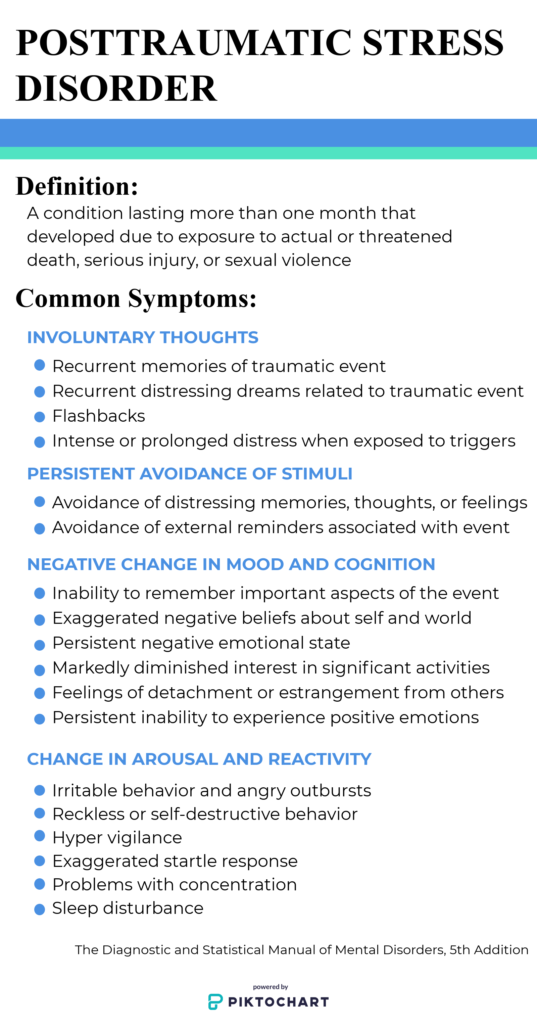

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Graphic by Kelsey Johnson

With every cry of her baby, Lehi resident Hailey Allen, 33, felt like she was being stabbed.

“I felt so out of control,” Allen said. “I didn’t know how to fix it, I didn’t know how to change it, and so I blamed myself. Instead of thinking ‘this is the baby trying to communicate with me,’ I took it as another sign my failure and that I was being attacked.”

Allen has four kids under the age of 10 and, despite suffering the same feelings with almost every birth, Allen didn’t get help until turning 30. It was then that she found out she was suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder.

Allen experienced childhood abuse from her father as well as being raped while she was a student at BYU. She said both of these experiences continually plagued her throughout her life and she didn’t realize that that wasn’t normal.

“In my head, I always had my rape story and I didn’t realize that wasn’t normal. It just constantly played in my head,” Allen said. “I had my normal thoughts, and I had my dad’s voice, what he would say on what I was doing or what I was thinking, and then I had my rape story playing in my head all the time.”

Allen said that, although at the time she didn’t know why, being around her children as babies was incredibly triggering due to the traumatic events she had experienced. She said the expectation of giving everything, including her body, to her child without hesitation was essentially unbearable.

“Having children, having your body taken over by something else and being expected to sacrifice and to be okay with what is happening to you, is very triggering for any woman who has gone through sexual abuse or sexual assault,” Allen said.

This then led to every cry of her child becoming an “attack” on Allen where the sensory overload of her baby’s cries, on top of physical and emotional exhaustion, had her counting down the minutes to nap time or her husband’s return from work.

“When it got to be too much, I would put the crying baby in the crib and shut the door and put the blankets over my head. And I just needed to do that for a little while. And then I could go back in,” Allen said.

Despite the feelings of “surviving” and not enjoying motherhood, Allen said she continued to forge on without professional help or a diagnosis until 2015 when her repressed abuse memories began to resurface.

“I was 29, about to turn 30, when my PTSD, which again I didn’t know I had, spiked. So I can’t sleep, I’m having nightmares, I’m having flashbacks, I’m having anxiety attacks, I can’t leave the house, I can’t listen to the radio, I can’t read books. Everything is triggering me,” Allen said. “So I decided I needed help.”

After reaching out to the Crisis Center for Women and Children, Allen began counseling and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy, a psychotherapy approach commonly used to help trauma victims. Allen said her symptoms were so bad that it was necessary for her to take medication as well, which to her at the time was “devastating.” However, Allen said it proved to be invaluable, taking away the recurring images and voices in her head stemming from her traumatic past.

“I could take a shower and just be with myself as opposed to being in the shower and having this clear reminder of my rape story playing over and over again,” Allen said. “And I was like, ‘Oh! This is why people enjoy taking showers or time to themselves.’ Because for me, it was never enjoyable.”

During this time, Allen also created Helping SAVE, a nonprofit providing free “healing classes” to sexual assault and sexual abuse survivors and their support. The classes feature activities such as yoga, African dance and art, which, she said, gives individuals a safe place to try out new hobbies.

Enlarge

Hailey Allen

For Allen, the activities have been especially healing in her relationship with her own body.

“To be able to dance and to feel happy in my body was a huge moment for me, “Allen said. “Because I was carrying around all this shame and hate for my body because I was blaming it for all the abuse I had taken. Why didn’t my body protect me? Why did my body tempt someone to do this to me? So to be able to be happy and enjoy my body and have fun in my body was a huge moment for me.”

Allen said while she’s happy with where she is now, the road to recovery was “not easy.” When she began medication, she said it took weeks for it to kick in and required some experimentation with different types of medications in order to get the right kind for her, with random side effects happening along the way. Therapy brought emotions she’d held back to the surface, resulting in anxiety attacks and other emotional upsets. Allen said it was a “rocky time” for her and her marriage, but she was able to get through it with the support of her husband and unconditional love from her children.

Enlarge

Hailey Allen

Allen recently had her fourth child while taking medication and receiving counseling and EMDR therapy, and she said the experience was a “night and day difference” from her past postpartum experience before getting help.

“It’s taken a few years,” Allen said. “But I think we’re all very happy with where I am now.”

Fighting Shame with Compassion

Mental illness and motherhood is not an uncommon combination, but, according to Jones, women often feel shame for not achieving or experiencing everything they hope for or feel pressured to be. This “mom guilt” then heightens the feelings of not being good enough, feeding into a negative cycle.

“We sort of romanticize motherhood in our culture and sort of make it seem like motherhood should be the single most fulfilling thing in your life and bring you joy and happiness all the time and come easy to you,” Jones said. “But in my experience and the experience of a lot of people I see, it just doesn’t happen like that. It’s not always easy and it’s not always fulfilling.”

Family nurse practitioner Natalie Organ said at least half of her clients are mothers with mental illness and said she makes sure to tell them that “everything is a stage.”

“It’s okay not to like the baby stage. I didn’t like the baby stage. And I love my kids, I absolutely adore my kids, but I have no desire to have another baby again,” Organ said.

Jones said having a mental illness can mean that a mother needs to put more energy into taking care of herself by getting enough sleep, creating time for herself, avoiding social isolation, eating healthy, exercising, and asking for help when she needs it.

Organ said sleep provides a reset for everything and the lack of it makes mood disorders worse. Since everyone needs different amounts of sleep, she said to note when you go to bed and then let your body wake up naturally the next day in order to know how much your body needs.

Organ also advised that it’s always okay to say no, especially when your life seems to be consumed by all the activities you and your children are a part of. Instead, she says to make sure to take time to get out of the house and do something that makes you happy.

Jones said the two most common things that cause mothers to have a harder time are unrealistic expectations and not reaching out for support. In Jones’ opinion, raising a child requires a team and parenthood will never be easy or perfect.

“Be compassionate for yourself,” Jones advised. “Be easy for yourself. This is a really hard thing. Mothers have been struggling with parenting from the beginning of the world and this isn’t supposed to be easy.”