See also: Study shows Donald Trump’s linguistic style differs from traditional politicians

Americans watch political debates. A study conducted by The Annenberg Public Policy Center showed that in 2012, around 46.2 million viewers watched the first debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney.

Of these, six out of 10 viewers tuned in within the opening five minutes and watched until the debate was over. The majority of these spectators watched more than one debate, and 29% of people surveyed said debates were the most helpful in deciding how to vote.

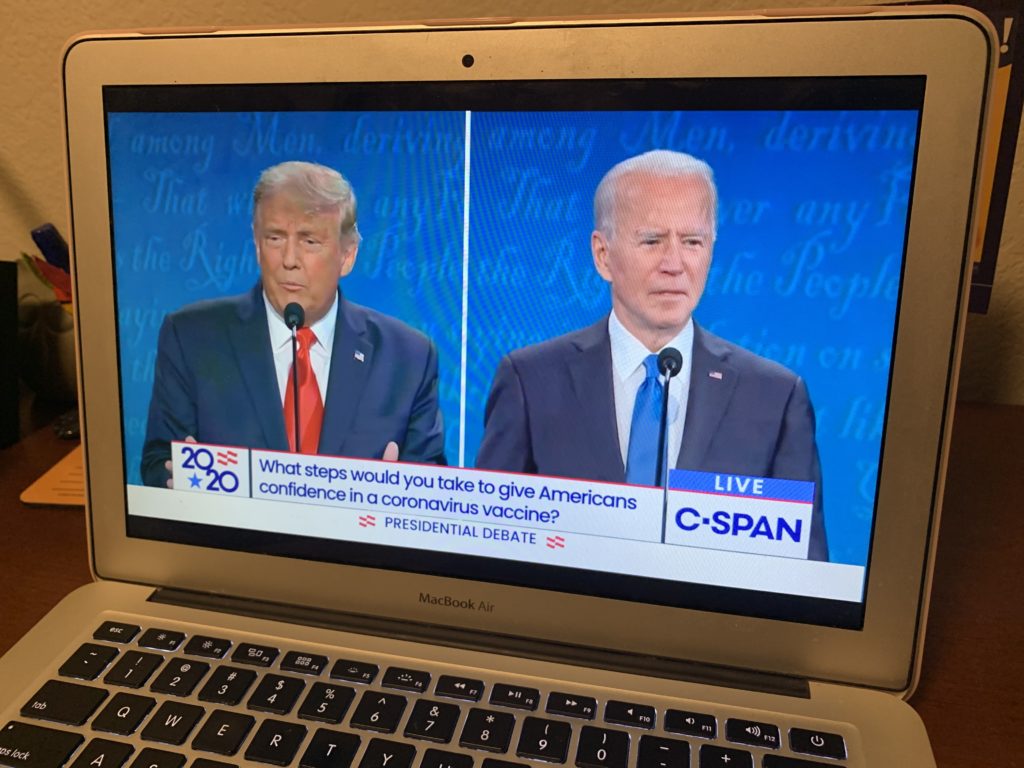

In fact, presidential debates have been an American tradition since John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon faced off on public television in 1960. In late September of 2020, there appeared to be no disruption to the common election debate, and President Donald Trump and Joe Biden took the stage.

However, the public reaction to the first presidential debate was mostly negative. Both candidates continually interrupted each other. They largely ignored time limits and topics suggested by the moderator. The second debate was then canceled in favor of separate town halls. Most sources attributed this change was to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, though some suggested campaign strategy may have been another cause.

This year’s debates, and the reactions to them, called the effectiveness of political debates on the presidential level into question.

LeReina Hingson is a linguistics professor at BYU. Hingson’s research is focused on language and the law, including politics and campaigning. She said she believes in the importance of words, especially as they pertain to the public perception of politics.

For example, Hingson said she is often surprised to hear people express confusion about the popularity of President George W. Bush among Hispanic voters. According to Hingson, Bush’s use of Spanish helped him connect with that particular group of constituents.

Hingson said presidential debates are designed as “opportunities for advertisement and persuasion.” In terms of persuasion, Hingson said power is usually observable. Power can be, according to Hingson, manifested linguistically in interruptions and the amount of talking time versus listening time.

As far as advertisement goes, Hingson said candidates often employ various tactics, including repetition and the framing of various arguments. She said she also watches for building cases with evidence versus jumping to conclusions.

Hingson said she believes debates to be effective. She singled out Trump for his particular debating style. She said he has taken advantage of being an “unpolitically correct” outsider. He has, Hingson said, become a sort of parody of the politicians and the way they present themselves. She said her opinion results from a failure of the political system, rather than a reflection on Trump himself.

She said his persona, and therefore his debating style, creates awareness of the shortcomings of American politics and society. In Hingson’s opinion, this, along with the COVID-19 pandemic, has increased general political involvement. The 2020 presidential election drew more voters than any previous race in U.S. history.

“So that goes to show, language is important and language is part of it, but the performance and overall image that you create, and your typical behaviors are going to also be a huge contributing factor,” Hingson said.

As a result, Hingson said she believes debates are here to stay, though not without some change.

“I think these kind of debates will follow the overall trend of politics, which is changing substantially, and which is largely unsustainable as it currently is,” said Hingson.

Jesse Egbert, a linguistics professor at Northern Arizona University, began a study about language in political debates in 2016. The study covered the speaking styles and strategies of both Hillary Clinton and Trump.

Egbert found that, based on every televised debate since 1960, Trump does have a novel debating style. According to Egbert, Trump often involved others in his language. Trump was likely to mention Clinton, the moderator, or the American people when debating.

The findings showed that Trump would often use vague language and take impersonal stances. He would identify a problem and state that something needed to be done, but remove himself from the solution or the problem. This ran contrary to other presidential debaters, who tended to use phrases like “I believe that…” or “I think we should…”.

Egbert said the first debate of 2020 “was like nothing we’ve ever seen in the history of debates.” He suspected that Biden’s team had studied Trump’s performance in 2016 in preparation, but noted that Biden seemed caught off guard by his opponent.

Egbert noticed that some aspects Trump’s debating style also appeared in the vice presidential debate. Egbert said that debate was more civil but said interruptions, especially from Mike Pence, were still common. Whether this trend will continue after the Trump presidency, Egbert isn’t sure, but he did note that Trump has been successful in some ways.

“I think Donald Trump’s off-the-cuff colloquial style of debating resonates with a lot of viewers who feel like they’re hearing from someone who understands them, and their language, and doesn’t talk in a way that they can’t follow or understand or relate to,” Egbert said.

However, Egbert also mentioned potential dangers of Trump’s approach. Trump often makes claims without sighting evidence, and Egbert said he believes his opponents and moderators should hold him linguistically accountable for this.

Egbert predicted that bickering and interruption will become less common in future debates and said he believes in the overall effectiveness of debates.

“I wonder if they’re more effective for the style that they allow candidates to portray and not so much for the platform that they give candidates to share their political positions,” said Egbert.

Josh Tillman had a different experience. Tillman is the president of the Speech and Debate Club at BYU. He works with students to coordinate and practice for competitive debates. As a club, they focus on formal elements of debate, as well as rhetoric and philosophy.

Tillman said he is an avid debate viewer, but turned off the first debate after the first half. Based on what he saw, he deemed the rest not worth watching. He noted that the second debate was more civilized, but does not feel that either contest did much to sway voters.

“This is probably due to the candidates and the format in part, but it’s also probably contributable to the changing political climate with less and less middle ground and more people gravitating towards the political poles of the two parties,” Tillman said.

Tillman said he tends to analyze debates in terms of ethos, pathos and logos. In terms of the first Trump versus Biden debacle, Tillman signaled out ethos, or emotional appeal. Tillman said Biden used ethos when conjuring up images of COVID-19 deaths, and Trump followed suit by presenting himself as a victim of the media.

In terms of policy, Tillman preferred other viewing options.

“The best part about the vice presidential debate is that you take out a lot of the character bashing and really just get down to the policies,” said Tillman. “If you watch (Mike) Pence and (Kamala) Harris you’ll actually see them defend the policies with statistics and arguments for their efficacy, and honestly I think vice presidential debates are the thing to watch to understand a presidential candidate’s platform.”

Despite his opinions on the performance in this year’s debates, Tillman said still believes in debates as an institution of democracy.

“At the heart of democracy is agonism, the idea that two things clashing will help the better one to prevail, and debate ideally helps democracy flow better and run smoother by facilitating agonism. Free speech and lively debate are a large part of what has made this country what it is, and I truly believe that those things done right will continue to move it forward,” Tillman said.

Faculty member Ben Crosby advises the Speech and Debate Club at BYU. As a professor, his research focuses on political rhetoric. Crosby participated in debates in high school and college.

Crosby referred to presidential debates as “political theater, and said the format for collegiate debates is very different, in that participants must cite sources. College debaters are not vying for popularity. Instead, they are trying to win points from judges.

Crosby said presidential candidates use evidence as a tactic to impress audiences. He noted Trump’s ability to quickly make claims and data that appeal to voters, but said he was disappointed in the lack of sources and accountability in real time.

Crosby acknowledged that Trump was fact-checked after the debates occurred. He added that, in the moment, false claims don’t matter to most viewers as long as the candidate says appealing things. As a result, Crosby said he believes political debates to be ineffective.

“As the country gets more and more polarized, decisions are made typically before these debates happen, and the debates tend only to confirm people’s existing opinions or preferences,” Crosby said.

He said incorporating some aspects of traditional college debates into political debates would improve the overall quality. For example, Crosby would allow a moderated cross-examination period and implement real-time fact-checking. Crosby said debate education for all people would make the world a better place.