Editor’s note: this story pairs with “4 ways to protect privacy online”

Internet users’ questions about information privacy are getting more heated after the data of more than 50 million Facebook accounts was reportedly handed over to Cambridge Analytica, an analytics company the Trump campaign hired in 2015 to send out targeted ads.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg publicly admitted to the data misuse on March 21, according to the New York Times. The Times reported it as the first public confession to the misuse of user data.

With this new development and the current investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election, both users and stockholders are scrutinizing Facebook’s privacy practices.

Lawyers Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis famously defined privacy as “the right to be let alone” in their 1890 article for the Harvard Law Review.

Yet, privacy — specifically, information privacy online — can mean much more or much less than that, according to Leslie Francis, a distinguished professor of law and philosophy at University of Utah and coauthor of “Privacy: What Everyone Needs to Know.”

What privacy rights internet users have and value is controversial, Francis said, and what harm comes from breaching that privacy has drastically changed since its 1890 definition.

What is privacy now?

Researchers France Bélanger and Robert Crossler defined information privacy as “the desire of individuals to control or have some influence over data about themselves” in their 2011 article for MIS Quarterly, an academic journal about information technology.

However, Francis said privacy shouldn’t be considered simplistically.

“Underneath the idea of privacy there are a whole lot of different concepts,” Francis said. “One is private space … another is control over information, another is various kinds of protections from being surveilled … (and) another … is the protection from interference in the important choices that you want to make about your life.”

According to a 2016 study by the Pew Research Center, 74 percent of Americans said it was very important to them to be in control of who has access to their personal information.

“If the traditional American view of privacy is the ‘right to be left alone,’ the 21st-century refinement of that idea is the right to control their identity and information,” said Lee Rainie, one of the study’s authors.

BYU information systems professor Mark Keith said privacy today is less a state or a right and can be viewed more accurately as a bargaining tool.

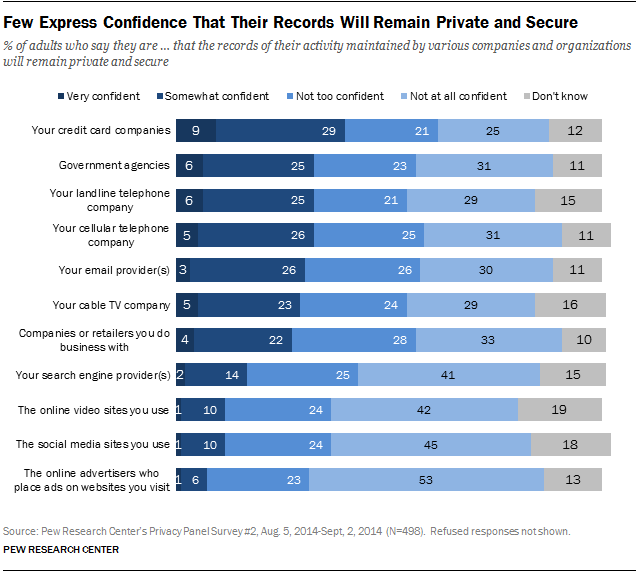

“Today it’s morphed into more like privacy as a commodity, meaning that it’s something that can be bought, sold and traded,” Keith said. “As companies have realized the value of information, that’s shaped the way we look at information privacy now.” Timeline by Eleanor Cain Contrary to popular belief, Keith said younger people are more likely to care about their privacy online than older generations. The same 2016 Pew study also pointed out young adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely than their elders to be focused on digital privacy and to have taken steps to protect information privacy. Yet, a “privacy paradox” is often present among users, a review of information privacy research noted. “Despite reported high privacy concerns, consumers still readily submit their personal information in a number of circumstances,” the review read. Keith said the prospect theory from behavioral economics can explain why users don’t act rationally with their information privacy, even if they value privacy. Keith compared the paradox to a gambler. When the gambler wins money, he takes fewer risks; when he loses money, he takes even more risks, despite the fact that the risk factor of winning or losing is the same for both the loser and the winner. Rather than act rationally with his money, the gambler acts on a “bounded rationality” where reference points influence his decision making. The gambler, Keith said, acted irrationally because he wanted to get back to his original “reference point,” or sum of money. “(People) behave just like the gambler with their personal information; they’re not rational,” Keith said. “And the reason why is because there’s information asymmetry; they don’t understand what the providers intention is with that data.” Listen to Keith’s full explanation of his experiment that proved the gambler concept applies to users protecting their information. Information asymmetry between users and providers often exists because providers aren’t incentivized to tell users what they’re using their data for, Keith said. When they do, users are much less likely to give out their information. This creates a lack of trust from the user about the provider, since users can’t know where their personal information will actually end up. This can be the basis for legitimate concerns about information privacy, Keith said. BYU Law professor Clark Asay said providers can be ambiguous about what they’re doing with users’ information because the United States is a “self-regulatory regime,” meaning it’s mostly left up to each provider with how they treat user information, as long as they put it in their privacy agreement. However, even privacy agreements can be confusing and reveal very little, Asay said. “Even if you read it, you still wouldn’t have very much insight about what exactly is going on with the information that’s being collected about you,” Asay said. “But that is sort of the legal basis in the U.S. for a lot of the privacy invasions that occur that are OK under the law.” Asay said information-gathering practices are often legal, even though users perceptions about the practices may be negative. Little can be done about infringements on information privacy until a user can prove “tangible harm.” “Harm is probably the biggest obstacle to having more privacy online because courts and regulators don’t really recognize the harm, and people have a pretty hard time articulating it,” Asay said. Real harm is out there though, Keith said, even if it’s only potential harm at the moment. “Information matching is a lot easier than people think,” Keith said. “If someone gets one type of data they can often use it to either tie it to other accounts somewhere else on the web or predict other things about you that could then be more dangerous.” Keith himself did a experiment to prove how much information could be collected about a person just from location data. He had students download a mobile app he created, but he instructed them not to open the app. After several weeks, Keith predicted various aspects of the students’ lives including race, relationship status, income level and political preference with accuracy — all because the students agreed to allow the app to use their location data when they first downloaded it. Few Americans think their information will remain private or secure, and 64 percent believe current laws aren’t good enough protecting privacy online, the Pew Research Center found. Yet, Asay said he doesn’t see the U.S. becoming more like the European Union, where a single agency monitors all data privacy unilaterally. Over-regulation could stifle America’s innovation and growth, he said, and could possibly make users pay for free online services they now take for granted. “We say that we care about privacy, but put our money where our mouth is and I don’t think most people actually do that much because there’s no harm,” Asay said. “Or there’s not harm such that it’s outweighing the benefits that we want.”How do users value information privacy?

Perceived, potential and actual harm

Information privacy in the future