Editor’s note: this story pairs with “Parents immersing themselves in adopted children’s culture”

Daniel and Linda Hardman both grew up in large families with eight kids each. They knew they wanted a large family of their own. When a doctor told them they could not have any more biological kids after the birth of their first son, they decided to adopt.

Daniel and Linda are white. Most of their adopted kids, however, are not.

According to sociologist Cardell Jacobson, “people are adopting cross-racially and transracially more and more.”

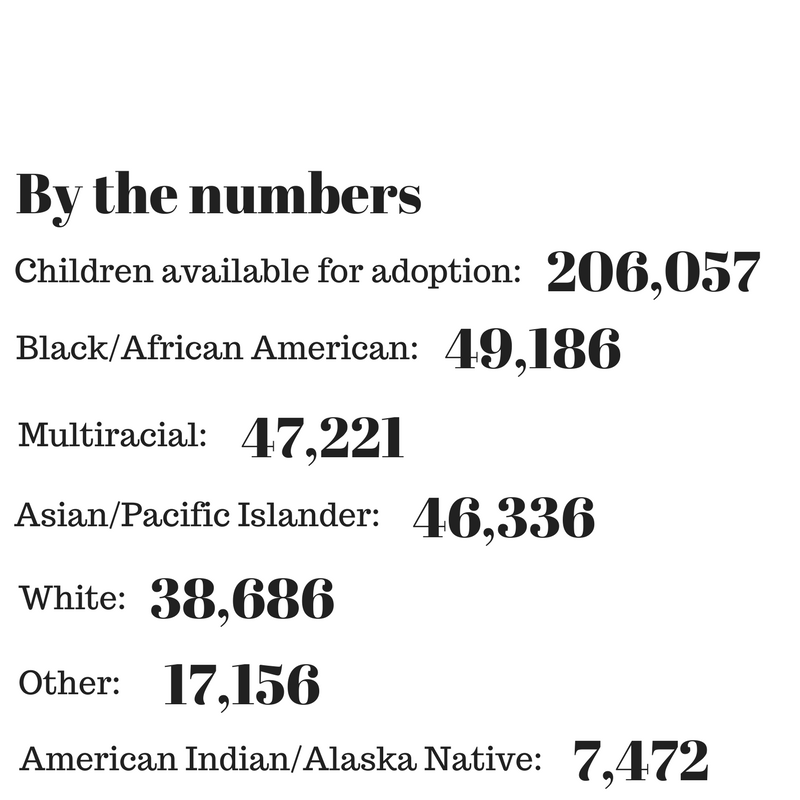

According to a 2017 study, only about 19 percent of children available for adoption are white. But 84 percent of adoptive parents are white.

The adoption services the Hardmans used give prospective parents the option to indicate whether they want to adopt children that look like them.

“I remember the conversation where we said, ‘Do we want to try and restrict this?’ and we were like, ‘No; why would we do that?'” Daniel said.

In addition to their oldest biological son, Ethan, the Hardmans have two adopted African-American children, two Haitian children, a Taiwanese daughter and one white son.

Linda said they wanted to leave the option open because they “just wanted the Lord to send us the kids that were our kids.”

“We did not try to build a family that was this diverse; that wasn’t our goal,” Daniel said. “It just came out naturally from us being open to adopt whoever seemed like the right circumstances.”

There are more black, multiracial and Asian children to adopt than white children.

By comparison, parents looking to adopt children are overwhelmingly white.

Non-white kids in a white world

Janet and Martin Monks, however, weren’t just looking to adopt any child.

The Monks already had five biological children, but after Janet visited an orphanage in China filled with abandoned baby girls, she wanted to make a difference.

“We wanted to adopt a Chinese daughter because there were so many of them that needed a family,” Martin said. “We just wanted to bring one baby out of those orphanages.”

Janet and Martin’s daughter, Kylie, said once while grocery shopping with Janet, a stranger assumed Kylie was an exchange student.

“You can’t just assume that about people,” Kylie said.

Kylie said she just laughed it off at the time.

The Hardman kids often laugh at people’s misconceptions, as well.

But not everything can be easily brushed off.

Caleb Hardman is white. He said once in elementary school a kid bullied his Haitian brother, Sean, and called him a racial slur. Caleb punched him in the face.

“I was like, ‘Call my brother the n-word again and I’ll kick your teeth in,'” Caleb said.

The elementary school principal called Caleb into the office to ask what happened. Caleb explained that a bully had called his brother the n-word. Caleb said the principal didn’t believe that Sean was his brother.

Caleb and Sean were pulled out of school and their mom picked them up.

“I remember Mom bought us milkshakes,” Caleb said. “Dad was like, ‘You can’t do that; you’re rewarding them for bad behavior,’ and Mom was like,’ No, I’m not.'”

The whole family laughed at Caleb’s recollection of their mom’s reaction.

“I don’t think (that kid) ever gave Sean crap after that,” Caleb said.

Dylan sometimes takes a different approach.

“If they’re trying to be offensive then I’ll just say, ‘I can get you in trouble really easy,'” Dylan said.

And Dylan said Sean is now a football running back, “so they don’t (mess with him).”

Family: stronger than skin color

Jennifer Kelly suffered from postpartum depression after the birth of her first two children, but she knew she wanted more kids. She and her husband decided to adopt.

Like the Hardmans, Jennifer Kelly and her husband also indicated they were open to adopting children of any race. Their three adopted children are all African-American.

Kelly’s experience is different when it comes to her kids. Aside from teaching her children about Martin Luther King Jr., slavery and the Emancipation Proclamation and answering any questions her kids might have, her family hasn’t yet dealt with targeted racism.

Kelly lives with her husband and children in Guatemala.

“Maybe that’s because we have always homeschooled and live in a foreign country,” Kelly said. “(Racism) is something I don’t dwell on or bring a focus to, because that can create children (or) adults who are always on the defensive and looking for others to treat them differently.”

BYU social work professor Jini Roby agreed that focusing on racism may make children more sensitive, “when it really may not have anything to do with racism when people react negatively to them.”

Roby said racism is present in different forms in society, in some “circles” more than others. She suggested parents focus on building them self-confidence and self-worth instead of warning children about racism.

She also emphasized the importance of parents building a strong relationship with their children so they are comfortable coming to them if they are ever targeted by racism.

“(It’s) not to say that racism doesn’t exist,” Roby said. “I think it’s really important that children feel comfortable with who they are, and that they understand why they’re different-looking from their parents, and really emphasize their relationship (with parents) and really work on attachment and good communication.”

Roby said parents need to be prepared to deal with racism towards their child when it happens.

Kylie doesn’t feel like she has ever been targeted for being Chinese, except for when people assume school and grades come easily to her. She was recently accepted into the Southern Utah University nursing program.

“I work really hard (for my grades),” Kylie said. “When people assume that I don’t have to (work hard), I feel like that’s unfair.”

Martin Monks said people have told him, “you did a good thing, adopting a girl from China.” He disagrees, saying he and his wife feel Kylie was always supposed to be a part of their family.

“Honestly, she’s been more of a blessing to our house and our family than I think we’ve been to her,” Martin said.

For the Hardmans, the feeling is similar. They can’t imagine their family looking any different or having one less child.

“They’re our kids,” Linda said. “That’s it.”