Kyra Torres began working at an assisted living home when she was 16, making $9 an hour. After a year, she was given a $1 raise.

But when her friend Chris began working there, he was started at $11.50 an hour, despite her having “significantly more experience” than him, Torres said.

“We weren’t supposed to talk about how much we were making when we worked there, but me and Chris were friends,” said Torres, now 20 and married to Chris. “I just got annoyed and kept working.”

Torres, who’s studying health promotion and education at the University of Utah, said she didn’t take any action.

“I just knew no one would care,” Torres said. “No one would’ve taken it seriously.”

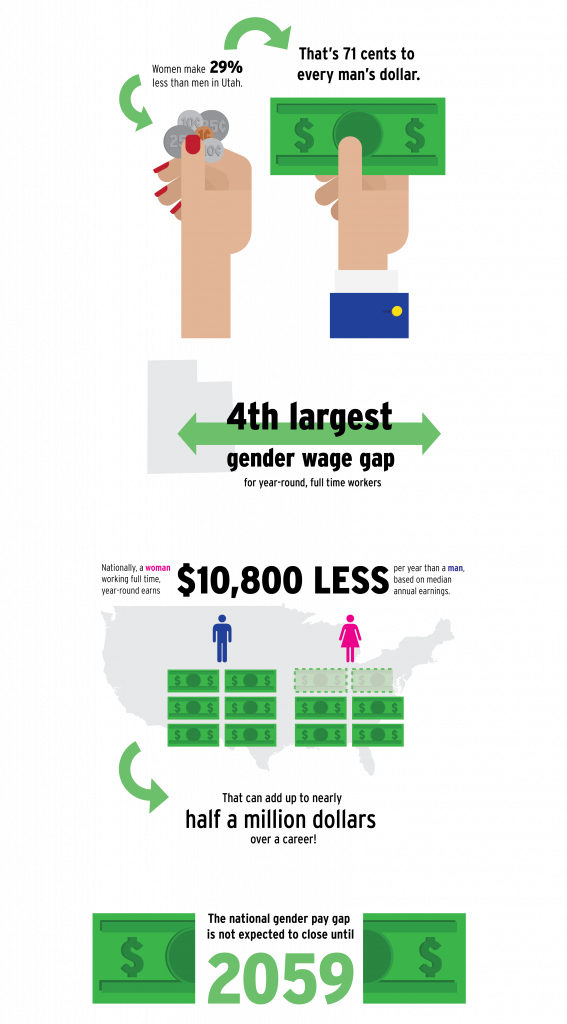

Utah has the fourth largest gender wage gap for year-round, full-time workers, with women making 71 cents for every dollar a man makes, according to a brief and infographic from the Utah Women and Leadership Project. In addition, women make 29 percent less than men in Utah, compared to women nationally who make approximately 20 percent less than men.

However, when the United States’ gender wage gap is adjusted for factors such as job title, education and experience, the gap shrinks from 24.1 percent to 5.4 percent, according to a report from Glassdoor.

Numbers game

Kyle Robinson, an auditor for Price Waterhouse Coopers, said the problem with talking about the gender wage gap is many people misunderstand the numbers.

The oft-cited statistic of women making 79 cents to every dollar men make is only a comparison of what men make on average and what women make on average, Robinson said. The statistic doesn’t account for other factors that contribute to salary, such as industry, work experience and location.

“(The statistic) is an apples to oranges comparison,” Robinson said.

Robinson said there are instances of an equally qualified woman being paid less than a male counterpart, but these situations are rare and protected under the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

“The truth is, we hear this generic, vague ’79 cents to the dollar’ figure way more than we hear of actual specific cases of wage gap at a company,” Robinson said.

Robinson said that people should focus on specific instances of discrimination and companies that allow a gender wage gap rather than saying all American businesses are sexist.

“I feel like the whole (gender wage gap) movement is more about blaming and name calling than actual action,” he said. “If we want to close the gap, quit calling everybody sexist, and let’s encourage more women to pursue higher paying careers. … Or let’s simply realize that different jobs in different locations with different experience levels pay different amounts.”

Robinson said believing in a gender wage gap is counter-productive to working toward true gender equality because it takes focus away from real issues.

If people really want a woman’s average pay to be raised, they should encourage women to go into engineering, software and other high-paying fields, Robinson said.

Contributing factors

Many people try to discount the gender wage gap by saying a doctor’s wages can’t be compared to a secretary’s wages, said Robbyn Scribner, a researcher and writer with the Utah Women and Leadership Project. While Scribner acknowledges how the gender wage gap shrinks when other factors are considered, she still thinks the gap matters, regardless of how small it is.

“If (the gap) is based solely on your gender rather than your qualifications, your success, your expertise, then it shouldn’t be there,” Scribner said.

Scribner said Utah’s gender wage gap is the result of a variety of factors including educational success, type of education and time spent away from the workforce. She also said a large part of the gender wage gap is occupational segregation, meaning jobs dominated by men tend to pay more than jobs dominated by women. Specifically in Utah, she continued, more women go into female-dominated fields, which tends to affect the state’s gender wage gap.

She also said early socialization may play into why men and women dominate different fields. For instance, she said boys are praised for taking risks and are told, “You’ll get it next time,” when they fail. Girls, however, are praised for getting the right answer, sitting quietly and being obedient and are taught they have a lot of value if they’re perfect.

“Some of these high paying jobs are risky,” Scribner said. “They’re difficult, and girls and young women don’t see women in these fields, so the combination of early age socialization and just having a lack of role models … (means) they don’t believe that they can succeed in these areas.”

Scribner said another big part of the gender wage gap is that Utah women are more likely to work part-time than women in any other state.

“Part-time jobs don’t tend to lend themselves to being more successful, long-term careers,” Scribner said.

BYU economics professor Jocelyn S. Wikle said Utah women are less likely to earn professional or graduate degrees than Utah men, and they’re less likely to major in high-paying fields. This will ultimately reflect in the men’s paychecks, she said.

Wikle said many Utah women don’t finish school or don’t major in high-paying fields because they’re planning on motherhood instead of careers. However, she continued, the percentage of working Utah women is comparable to rates of working women in other parts of the country.

“So this idea that focusing on motherhood will mean that these women won’t be working is just not right, and so perhaps it would be a good idea for Utah women to understand they will be working even if it’s just part-time,” she said.

Wikle said women who don’t complete their education are at an employment disadvantage when they decide they need to work. According to the Utah Women and Leadership Project brief, this can lead to many Utah women working low-wage jobs to help make ends meet or to obtain benefits, “but they do not ever consider themselves on a career track, despite working for many years,” the brief reads.

Wikle said men need education on this issue so they don’t put women at a disadvantage when they’re in hiring positions, and women need to learn that they can work and still achieve their family and motherhood goals.

“Learn to be courageous, learn to just have confidence and plan for a future,” Wikle said.

Speaking up, making changes

Provo resident Elizabeth Huntsman said while working at a sign shop in Cedar City four years ago, the human resources department told her she could be fired for asking her co-workers about their salaries.

Huntsman said she found out that a new male hire, doing the same work under her same job title, was making twice as much as she was, even though Huntsman had been working there for five years. Her boss offered no explanation when confronted, and when she began asking around the office, she discovered the other women were also underpaid.

Huntsman’s sister-in-law, a lawyer, encouraged her to file a claim because it’s illegal for HR to say an employee can’t ask co-workers about their salaries. In response, HR hired their own lawyer to prove Huntsman wasn’t being underpaid.

The process dragged out for five months, during which time Huntsman was required to work over 80 hours a week with no extra pay. When she pointed out that her male co-workers weren’t being required to work that much, she was told if she wanted equality, she’d have to work for it. Huntsman ultimately dropped the case when her husband got a job in Provo and they moved.

“The best thing women can do is talk about their pay,” Huntsman said. “It is illegal for a company to tell anyone they can’t talk about their pay.”

Scribner said women need to be allowed to negotiate their salaries without being perceived as aggressive or unlikable.

“That’s going to take widespread cultural change to recognize that women need to negotiate for themselves,” she said.

Scribner said there are three key factors in closing Utah’s gender wage gap.

The first is helping girls and young women realize they have “a whole world” of options; the second is helping companies realize if they give women more flexibility to balance their work and home lives, the women will become great successes to their businesses; and the third is passing legislation to support better healthcare and stronger wage discrimination laws, Scribner said.

Scribner added that women should be paid the same as men simply because it’s right and fair.

“If you’re doing the same position, if you’re really successful, if you’re bringing the same value to your company, you absolutely should be paid the same as anybody else who is doing that job,” Scribner said.