This story pairs with “End-of-life journeys often create ethical questions for patients, families.”

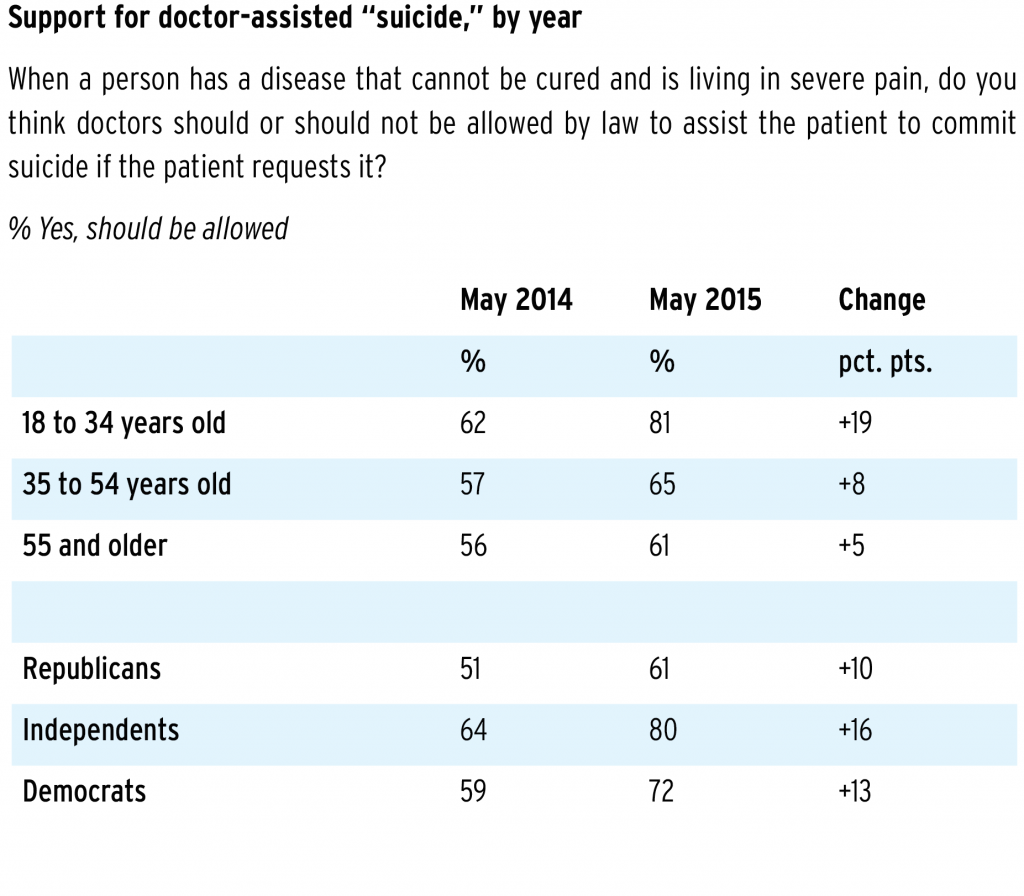

More than two-thirds of Americans support doctor-assisted suicide for terminally ill patients, according to a 2015 Gallup poll. Fewer Utahns — 58 percent — “somewhat favor” or “definitely favor” legislation for medical aid in dying for the terminally ill, according to a 2015 utahpolicy.com poll.

Under the “Advance Health Care Directive Act,” Utah law allows mentally competent adults to accept or reject health care procedures, even if their decisions result in an earlier death.

The act mandates that adults “be permitted to die with a maximum of dignity and function and a minimum of pain.” The act does not authorize mercy killing, assisted suicide or euthanasia.

Utah State Rep. Rebecca Chavez-Houck, D-Salt Lake City, has brought legislation before the Utah House of Representatives three times since 2015, calling for patients to be able to request life-ending drugs if certain qualifications are met. These qualifications include both written and repeated oral requests from a mentally competent patient who is terminally ill and over the age of 18.

Her most recent bill was introduced in January. Although none of these bills have passed, Chavez-Houck said many people have reached out and encouraged her to continue sponsoring the bill.

“I’ve had a groundswell of people all over the state — terminally ill patients who want this option, family members who have been through very horrific end-of-life journeys with their loved ones, people whose loved ones actually used very violent and tragic means to take away their life because they didn’t have this option,” Chavez-Houck said. “All of these people have come out and said, ‘Please continue to run this bill.'”

She first started looking into legislation because of emails from her constituents following the publicized story of Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old diagnosed with a terminal brain tumor who moved to Oregon in order to receive medical aid in dying.

Chavez-Houck said her biggest motivation is her belief that the patient’s agency should be respected above everything else. She said allowing medical aid in dying can prevent deaths that end more tragically.

“The tragedy and trauma that the family experiences when they find their loved one has taken their life in a very violent way is so different than what the experiences of people I’ve talked to have been with their loved ones as their loved ones take the medication,” Chavez-Houck said.

Rep. Michael Kennedy, R-Utah, is vice chair of the House Health and Human Services Committee. While he has deep concerns about the “intense and unimaginable” suffering patients and families go through, he does not support medical aid in dying.

Kennedy said he doesn’t believe the argument is about a person’s right to take their own life, but more about whether society should support that act.

Kennedy is a practicing family physician. He said there are many avenues a patient could take to end their life without legalizing medical aid in dying. For instance, a patient could lie to obtain and stockpile certain prescriptions.

He said people who support medical aid in dying are not necessarily asking for people to have a right to die, but for societal frameworks to allow it, such as allowing unhindered life insurance coverage or eliminating professional license and liability repercussions for those who assist in the process.

“(Supporters of medical aid in dying) want society to bless it,” Kennedy said. “They want society to foster it and support it. And that’s where I think society needs to take a stance and say ‘No, as a society, we promote life and liberty. We do not support death.’”

Kennedy said there would be a significant change to the medical profession if a medical-aid-in-dying law passed because clinicians are trained to preserve and promote well-being and longevity.

He said if doctors were involved in the philosophical aspects of death associated with medical aid in dying, it would lead to a very different ethical stance for the profession.

Rep. Brad Daw, R-Utah, chair of the House Health and Human Services Interim Committee, said he does not support medical aid in dying because it gives “physicians a doorway to killing people.”

“Once you start treating (medical aid in dying) as a medical treatment, it opens up a whole Pandora’s box,” Daw said.

He said legalizing aid in dying would cheapen life and denigrate what the medical profession is all about, and that it is unnecessary. He said patients might not want to end their lives, but family members may talk them into it, and legalizing medical aid in dying would worsen this problem.

Daw also expressed concern about the possibility of insurance companies paying for the medication for medical aid in dying and refusing to pay for extended treatment or certain procedures because of cost.

When asked if it was likely for medical aid in dying to become legal in Utah, Daw responded, “Not on my watch.”

“I was raised to respect life, and I was raised to view life is sacred, and so I do,” Daw said.

Chavez-Houck says she understands many people don’t personally agree medical aid in dying is moral, but she believes everyone should have the chance to make the choice for themselves.

“I don’t think it’s for any of us to discern the way a person feels that they need to navigate their terminal illness,” she said.

Chavez-Houck also said data and research show it is inaccurate to say people would just give up on their lives if the choice was available. She said instead, they can live fully because they no longer have to deal with “horrific anxiety” about the way their life might end.

“These aren’t people who are giving up,” Chavez-Houck said. “They’re people who are fighters, but they also realize at some point they’re going to die and they just want that to be a bit different and with less suffering and with less horror for their families than what’s likely going to happen.”

States define their own “right-to-die” laws because of a 1997 Supreme Court decision establishing the “right-to-die” is not a constitutional right. Later that same year, Oregon became the first state to pass a death with dignity law, allowing the terminally ill to voluntarily end their lives through physician-prescribed lethal medications.

Whether through legislation, court orders or ballot initiatives, California, Colorado, Montana, Vermont, Washington and the District of Columbia allow physician-assisted death as well.

California’s End of Life Option Act became effective in June 2016, allowing physicians to prescribe life-ending drugs to terminally ill patients. In the six months following, 111 individuals ended their lives, according to the California Department of Public Health’s report.

The report said of the 111 individuals, 87.4 percent were 60 or older, 72.1 percent had some sort of college degree and 89.5 percent were white. The majority had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. A total of 173 doctors reported prescribing life-ending drugs to their patients, according to the report.