The times they are a’ changin’.

Though the new Nobel Prize in Literature winner Bob Dylan crooned the 1960s anthem decades ago, the same sentiment applies today to women at home and in the workplace.

According to a study by the Pew Research Center, in 46 percent of two-parent households, the mother and father both work full-time, compared to 31 percent in 1970.

But the study also reports that 4 in 10 full- or part-time working moms said being a working parent has made it harder to advance in their careers. Sixty percent of working mothers said “balancing family and job responsibilities is very or somewhat difficult.”

Women in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints play a unique role in this conversation. For many years, the cultural rhetoric heard and shared among many LDS women was to get an education, but to become a stay-at-home wife and mother.

“The husband is expected to support his family and only in an emergency should a wife secure outside employment,” Spencer W. Kimball taught at a fireside in 1973. “Her place is in the home, to build the home into a heaven of delight … I beg of you, you who could and should be bearing and rearing a family: Wives, come home from the typewriter, the laundry, the nursing, come home from the factory, the café.”

Sydney Smith Reynolds delivered a Brigham Young University Forum address in April 1979 in which she encouraged women to pursue an education, but not necessarily a career.

“I am a full-time wife and mother. I am also a college-educated woman,” Reynolds said. “I am happy to be both, and have never found the two incompatible.”

In an Oct. 1996 General Conference address, President Gordon B. Hinckley said, “there are some women (it has become very many in fact) who have to work to provide for the needs of their families. To you I say, do the very best you can. I hope that if you are employed full-time you are doing it to ensure that basic needs are met and not simply to indulge a taste for an elaborate home, fancy cars, and other luxuries. The greatest job that any mother will ever do will be in nurturing, teaching, lifting, encouraging, and rearing her children in righteousness and truth. None other can adequately take her place.”

Yet Naomi Watkins said times have changed, particularly for many Latter-day Saints who are navigating a new norm.

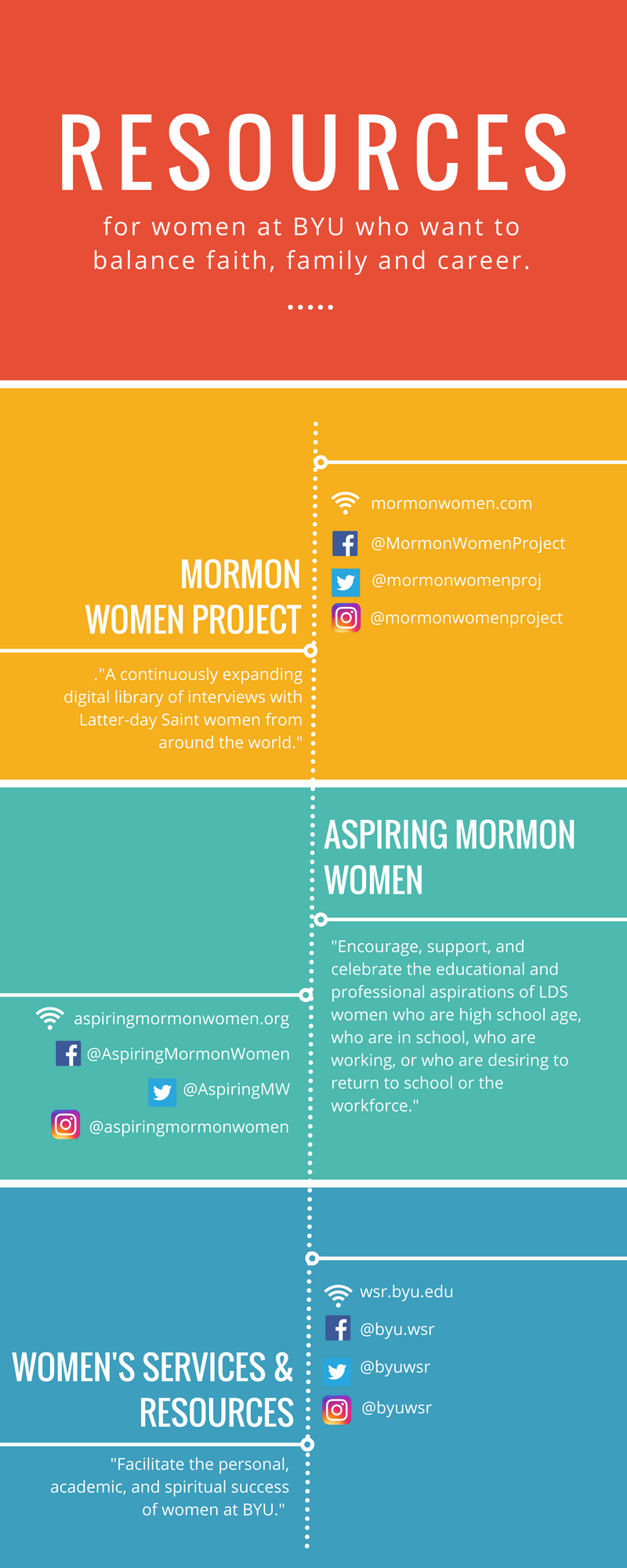

Watkins is a BYU graduate and the co-founder of Aspiring Mormon Women, a nonprofit providing resources for Mormon women seeking to pursue education and balance faith, family and career. She said women in the church are now being encouraged to pursue a valuable education and seek revelation as to how that education fits into their life.

“We’re definitely living in a different world, and our generation of women is very removed from that rhetoric,” Watkins said. “Now we have members of the Young Women’s General Board and other women who are highlighted in church leadership positions, like Elder Renlund’s wife, who is a mother and a lawyer. They are showing women that there are different ways to do things.”

Despite encouragement in recent years from church leaders, including from President Gordon B. Hinckley, some married female college graduates, especially BYU graduates, may feel wanting to pursue an education and a career is at odds with their faith and their divine roles.

Julie de Azevedo Hanks, Ph.D, dubbed this phenomenon “aspirational shame.” Hanks is a licensed psychotherapist, author, songwriter, wife, mother and owner and director of Wasatch Family Therapy. She wrote a blog post for the Aspiring Mormon Women website about this paradox.

“Did I have to choose between having a family and having a career?” Hanks wrote. “This paradox created what I call aspirational shame, the belief that my desire for achievement outside of the home meant that I was not a good woman, not a good mother, not a good wife and not a good person. I have carried some version of aspirational shame with me for decades.”

Watkins said she believes one way for single and married female students to be confident in their post-graduate pursuits, whether that includes motherhood, a professional career or both, is to seek out female faculty while at BYU.

“Learn from them,” Watkins said. “Those women will be your mentors.”

Julianne Hall Gray is a recruiter for the MBA program at BYU. She is married, pregnant, and plans to return to work after having her child. She recently hosted a Provo meet-up for Aspiring Mormon Women.

“Life isn’t an either/or,” Gray said. “You don’t have to have it all figured out right now.”

Jordan Jacobson studies commercial music at BYU. He said cultural perceptions about women’s role in the workplace and in the home can be deeply rooted in individual upbringing, and that men in the church have a responsibility to overcome these cultural stigmas as well.

“As far as my role as a man in the church, I feel like I need to support women in whatever they do,” Jacobson said. “My mom always worked, and she’s a fantastic mom; I feel like when people don’t support that, it’s just ridiculous.”

Melanie Steimle is a 35-year-old single woman who works at BYU’s Career Services. She also attended the Provo Aspiring Mormon Women meet-up. Steimle shared some of the experiences she has had while encouraging female college students to plan for the future, but not let their expectations of marriage and family limit their career choices.

“These decisions are so individual,” Steimle said. “The Lord’s path for you may not be the path for someone else.”

Watkins said the key to overcoming aspirational shame is as simple as respecting individual revelation.

“We talk a lot about the process more than the product,” Watkins said. “If you honor the process that someone is using to make decisions and receive personal inspiration, you should honor the outcome, no matter if it’s different than your own.”