The wavering of millennials in America’s religious landscape may not only be an issue, but also a question begging an answer. Where is everyone going? And what’s working to bring them back? To find answers, a team of Universe reporters spent a semester talking to religious experts around the country and to millennials themselves. What they found will be presented in upcoming articles.

Second in a series. Part one deals with the rise of the ‘nones.’ Part three discusses ways religions have appealed to millennials. Part four reveals millennials who stay with religion. Part five looks at millennials within the LDS community.

Shannon Hall-Bulzone is a 31-year-old ex-Jehovah’s Witness who didn’t “want to be the problem worshipper” in her congregation.

“I don’t think you have to be a member of a man-created religion to have a relationship with God,” Hall-Bulzone said.

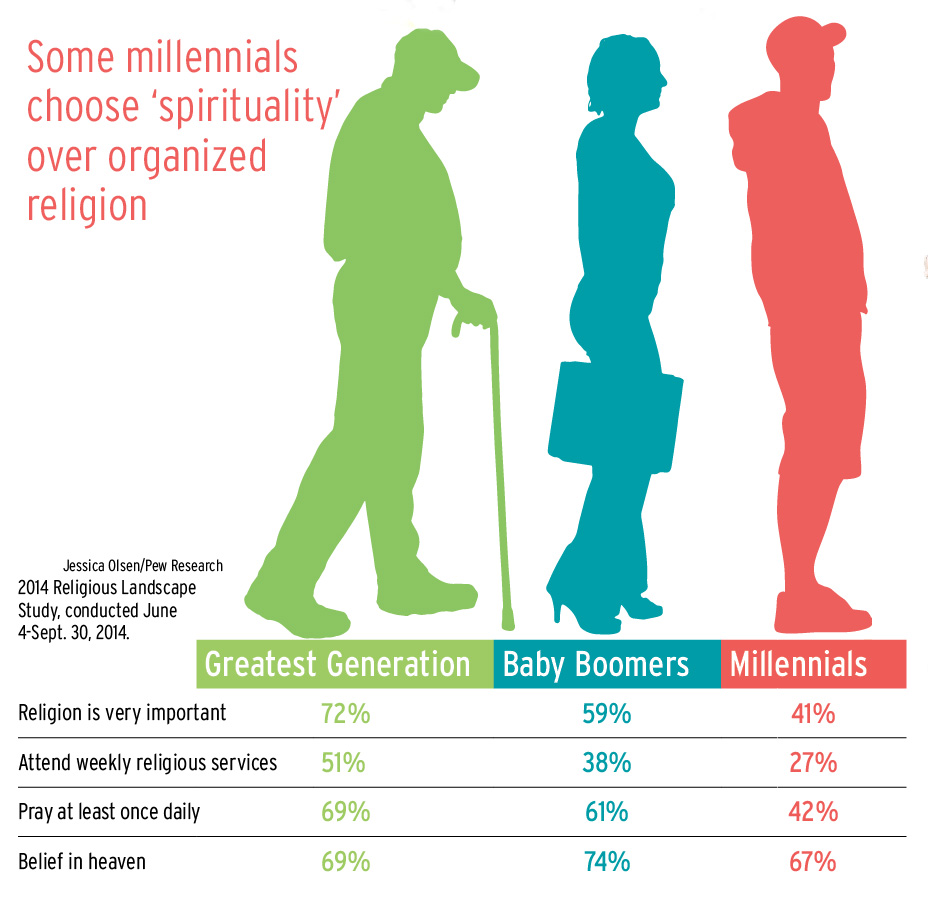

Instead, like 35 percent of her millennial peers, she’s chosen not to participate in organized religion at all.

Why the millennial disenchantment with organized religion? Like Hall-Bulzone, many millennials take issue with organized religion for both social and intellectual reasons, according to a recent Pew Research Center study. Some choose personal spirituality over formal, organized religion; some adopt a “cafeteria” mentality with their current church; others disassociate themselves completely.

According to the study, the “none” phenomenon when it comes to religious affiliation is more common among millennials raised in Christian and mainline Protestant churches. The study found that Hindu, Muslim and Jewish faiths have the highest retention rates of young adults who identify with the religious tradition in which they were raised. The study reported, for example, that 80 percent of Hindu young adults remain in their religion, while only 45 percent of those raised as mainline Protestants do so. For the LDS Church, the study shows the retention rate is 64 percent. The lowest retention rate is found among young Jehovah’s Witnesses — only 34 percent of whom retained their affiliation.

The moral pillars millennial ‘nones’ reject

According to psychologist Jonathan Haidt, moral foundations underlie all religious and political beliefs. In a 2008 TED Talk, Haidt explained five key values, but has since expanded his theory to include one more foundational value. The values and their opposites consist of care/harm, fairness/cheating, liberty/oppression, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion and sanctity/degradation.

Haidt suggested liberal thinkers privilege “care” and “fairness” over the other values, while conservatives tend to embrace the entire value system.

Haidt’s theory might explain why some young adults are moving away from organized religion. Pew Research shows that millennials are markedly more liberal than their predecessors. Fifty percent of millennials affiliate with the Democratic party, while 34 percent align with or lean toward the Republican party. So, it’s possible that millennials experience this pull to the liberal values of “care” and “fairness.”

This trend produces what may be a difficult pill for conservative religious leaders to swallow. The “care” and “fairness” principles can easily exist in an individual’s life independent of religion. Monsignor Francis Mannion, a retired Catholic priest from Salt Lake City’s St. Vincent de Paul Parish, attributes the millennial focus on care and fairness to “a rather pragmatic kind of moral system.” He said virtues like sanctity and authority-observance demand strong commitment, sacrifice and change.

“But we live in a consumer culture,” Monsignor Mannion said. “And people see no reason to consume or be involved in anything which is demanding of them.”

Neylan McBaine, author of “Women at Church,” sees a profound shift in spirituality, one that doesn’t rely on community as much as personal journeys and “the belief that churches can morph to reflect personal journeys.”

“Originally it was about morphing to an institution,” McBaine said. “Now people are shopping for institutions based on what they currently believe and want.”

Millennials: Lazy or analytical?

Does the millennial avoidance/personalization of religion mean that 20- and 30-somethings today are just lazy? Sam Sturgeon says no. He works as director of research at Bonneville Communications, a niche advertising firm that helps non-profits speak to people of faith who value family. Sturgeon spends a lot of time researching millennials and how they relate to religion.

“You hear a lot of people talking down to millennials, saying we have the dumbest generation,” he said. “But it’s not laziness and failure to grow up. They’re finding strategic ways to navigate the current situation they’re in. As I look at the research, millennials are savvy.”

Sturgeon questions the accuracy of the baby boomer fear that millennials delay marriage and big life decisions because of the “failure to launch” phenomenon. Perhaps it’s just strategy. “They say, ‘Yeah, my mom and dad got married young and they hated each other’,” Sturgeon noted. “One in 3 millennials, their parents are divorced. One in four millennials are born outside of marriage.”

Not wanting to mimic their parents’ mistakes, Sturgeon said some millennials bring a jaded, cautious awareness to their life choices, religiosity included.

Devin Willie, a 26-year-old Latter-day Saint, attends church services even though he no longer agrees with everything the church teaches.

Willie sees his generation as the first to be raised on postmodernist principles and believes “it’s catching up.” Postmodernism, marked by skeptical interpretations of reality (culture, philosophy, literature, art, etc.), drives the rallying cry of millennials today.

Postmodernism prizes personal realities and relativism, privileges concrete encounters over abstract principles and “lacks the optimism of there being a scientific, philosophical or religious truth which will explain everything for everybody,” according to PBS.org’s “Faith and Reason” glossary.

“We’re taught to question everything, not assume anything and find rational explanations,” Willie said. “I think it’s not incompatible with faith. It’s incompatible with dishonest and flawed explanations of where our faith has come from.”

Sam Savignac, a 23-year-old student in Bloomington, Illinois, shares Willie’s practice of questioning everything, including his faith. His father is Catholic and his mother is Unitarian, but he said he refused those religions and “found (his) own set of beliefs within (himself).” Today Savignac identifies as an “atheist animalistic pagan.”

“I grew up in a Christian family and when I looked to the sky and listened for God, I felt silence,” Savignac said. “But then I heard a song from the Earth under my feet … I have developed my beliefs by listening to that song.”

Roots of the millennial mentality: Institution-aversion

The millennial shift away from organized religion may also sprout from a distrust of structure. Postmodernists love to deconstruct, after all. According to Josh Packard, professor of sociology at Northern Colorado University, author of “Church Refugees,” and organizer of the “Dechurched” project, millennials avoid most social institutions — not just religious ones.

“The story that we’re seeing about church decline is not a church story, it’s a society story,” Packard said. “People no longer organize their lives primarily through large social institutions … that marks a major difference in our society, even from 10 or 15 years ago.”

McBaine explained that 20-somethings today don’t have a central enemy. Remember the old adage about a shared foe uniting a group in a common cause? That doesn’t really apply to millennials. In years past, world wars and central enemies created a country where people were more committed to institutions.

“But for millennials, there’s very little sense of that permanence; we haven’t had a central enemy that people are rallying around,” McBaine said. She attributes this in part to technology’s ability to humanize enemies: share their stories, show their faces. It’s not as easy to vilify a whole people anymore. “An example is with military conflicts; millennials are very hesitant to say Muslims are our enemy,” McBaine said.

So with religion, millennials are left asking themselves, “What is the role of this institution?”

McBaine suggests this generation expects churches to be a mechanism for social good. Millennials want to align with organizations that help them help other people, as opposed to rallying against an enemy. This mindset aligns with the liberal and millennial tendency to privilege “care” over other moral pillars.

But sometimes millennials “perceive the church as something much more insular, something less tangible,” according to McBaine. So, some wonder, if a church doesn’t seem to be an adequate welfare-provider or reflection of an individual’s personal journey, what purpose does it serve?

Searching for concrete answers

While tolerance is a common theme preached across the pulpit, churches across all religions still struggle with how to include members who may not fit the traditional churchgoer mold of the past.

Millennials experience higher levels of depression both in college and in the workplace than previous generations. However, few churches know how to address mental illness and support members who are struggling with it.

Austin Berlocher, 22, a student living in Champaign, Illinois, was raised in the Roman Catholic faith but left when his church’s answers started sounding “hollow.”

“I battled for years (and still do) with depression and anxiety, and all the church told me to do was trust God,” Berlocher said. “That didn’t feel right; I didn’t know what the truth was but I felt like I couldn’t put that much faith in something I couldn’t see, couldn’t feel and couldn’t hold accountable.”

Berlocher tried to gain answers from his church, but when he raised questions during meetings and tried to spark discussions, he said he was met with pity. This reaction from his church community and lack of concrete answers prompted him to leave the Catholic church.

“Don’t label me!” Love, millennials

Maybe it’s doing millennials a disservice to keep calling them one term and to paint them with sweeping generalizations. They hate that. But it is necessary to document trends. In his documentation of millennial trends, Boncom’s Sam Sturgeon notes one consistency:

“By and large, millennials don’t wear their faith on their sleeve,” Sturgeon said. “They don’t like labels. They don’t want people to say, ‘Oh you’re Catholic, got it. I know everything I need to know about you.’”

This generation likes to make their faith their own, so Sturgeon said that’s important to remember when framing advertisements or having conversations with millennials. “Millennials really want to move beyond labels,” he said.

“Millennials are more likely to say their beliefs first and their affiliation second,” Sturgeon said. “Where it used to be the other way around.”