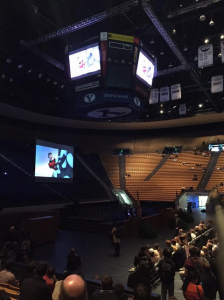

President of Pixar Animations Ed Catmull spoke on Jan. 27 to BYU students about the culture of creativity, failures and mistakes and working as a team.

Catmull was raised in Salt Lake City in the 1950s and wanted to be an animator since he was young. He said his hero was Walt Disney.

Catmull was an art major in college who decided to switch to physics, hoping it would help him learn about the animation details he wasn’t familiar with.

He needed to have a knowledge of everything that went into animation in order to reach his goal of becoming an animator.

The crowd laughed when he mentioned his switch from art to physics. This was a response he was used to when he told this story. The response is due to the fundamental misconception about teaching art in schools.

Art is not about learning to draw or blend color but “learning to see,” Catmull said.

He then tied this into what he defined as the fundamental question: “How do we see beyond our own preconceptions?” Catmull said many people think of creativity in a fairly narrow way. He said we need to “reframe creativity as solving problems … real problems.”

Catmull had the same goal for 20 years: to create a computer-animated film. In 1995, he succeeded with the creation of “Toy Story,” which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year.

“It doesn’t feel like 20 years,” Catmull said. “It feels like five.” After “Toy Story,” Catmull wasn’t sure what to do next.

“Having achieved my goal, I was now without one, and I felt lost. It was the internal feeling that I’d lost my compass,” Catmull said.

The Pixar president needed a new goal. Disney had just had huge success in film with the releases of “The Little Mermaid,” “The Lion King,” “Beauty and the Beast” and “Aladdin.” Disney fell into a lull for 17 years after this golden age.

Catmull noticed the Disney creators were smart people, but they were missing something that was essential to their survival: something subtle and hard to find. If this unseen force existed at Disney, then it must exist at Pixar too. With this discovery, Catmull was able to find his compass.

“How do we build a creative culture that’s sustainable?” became his new goal. In order to do this, Pixar needed to find and address blocks to creativity. To figure this out, he needed to address three points to creativity: the question of honesty, failures and mistakes and protecting the new.

The question of honesty

Catmull said people aren’t candid about addressing problems because they “want to be polite, show respect or don’t want to embarrass others or themselves.”

Because of this, many companies use a system called Brain Trust. This idea involved a group of people who weren’t too overpowering. This group needed to be a safe place for directors to share their ideas and films. The main role of the group was to give notes to the director that acted as “symptoms” to the problem.

The group never addressed the problem directly because it was the director’s responsibility to do that. Avoiding the actual problem also made it easier to avoid the question of honesty.

“We pay attention to power structure,” Catmull said. “That authority can screw up a room.” Catmull said that some experienced directors learn skills as to how they ignore notes from colleagues.

Every once in a while, Catmull said, “magic happens.” He mentioned the movie “Frozen” and the hurdles the group needed to jump in order to create the movie. He said these group meetings are never recorded, so the magic that happened can only be spoken about; and even then, it’s hard to explain.

Failures and mistakes

Catmull defined failure as having two different meanings. The first meaning was academic failures: trying something, finding it doesn’t and then learning from it. The second meaning was failures in school, jobs, projects and relationships: they all end badly.

Politics and business use failures to attack opponents. Catmull said failures are a necessary evil, though.

“If you aren’t failing, then you aren’t trying different things,” Catmull said.

Protecting the new

The crowd laughed when Catmull began this point with, “All movies suck at first.” He didn’t meant that the movie ideas were not necessarily bad, but that the movie was bad “in the sense that the film sucks.”

The creators of the movie come in with a film, and it almost always needs some work. Catmull said that when looking at a film, you can’t judge the film, but you can judge how well the team is working together — the spirit of the team. Teamwork is the most important aspect to creating a film.

Catmull entertained the audience by sharing the first version of the movie “Up.” This version involved a floating castle in the sky, where a king and his two sons lived. The sky kingdom was at war with the people on the ground. At one point, the two sons fell off the castle and onto enemy grounds.

While there, they came across a large bird. Catmull explained that this idea did not work very well.

“All that was left (from this version) was the bird and the word ‘Up,'” he said.

“Up” went from being set in a lost Russian dirigible (airship) to a strange land where the characters stayed because of a bird that laid magical eggs. Many changes were made before finally creating the story audiences are familiar with.

The film’s team was on a path filled with false turns and errors. “We had to protect this group while they built the undefined,” Catmull said.

With new ideas, there are bound to be errors. The idea of zero errors may be important in the aircraft industry or in medical work, but it is not important in animation. Finding the balance between not having any errors to having too many errors is where animation wants to be, but finding that spot isn’t easy.

“Where between zero and 40 errors should we be? I don’t know,” Catmull admitted.

The purchase of Pixar in 2006 by Disney led to another lesson in creativity. With the new eyes of the Pixar creators, there was now a better way to see what was going wrong with Disney. Disney was still in its 17-year downhill spin when Pixar came on board. The Disney team was dispirited and lost. Catmull knew that with a rapid success, it was easy to draw wrong conclusions.

“Your view of the world is now screwed up,” said Catmull, followed by a laugh from the crowd. Disney was also “feeding the beast,” or focusing on production, the biggest group in the story process. This group consists of cost, production and revenue. The studio lost its balance because of the focus on the beast.

Directors were given mandatory notes to help Disney get back on the uphill climb. Problems and balance were talked about in depth, and the company created a new Brain Trust (Story Trust in Disney’s terms). It took two years to get the Story Trust just right due to the mix of Disney and Pixar creators being put together, but once they experienced failure as a team, they began to bond.

With time, Disney was able to escape its lull. The company realized it was clinging to the past and needed to move forward. The company began to flourish once the creativity picked up and the teams worked as one. It completed a normally six-month project in four days.

“Don’t look back for excuses; look back for lessons,” Catmull said.

Catmull concluded with words of advice. People can learn from the past, but they shouldn’t dwell there. When solving problems in the workplace, people need to realize that problems aren’t an impediment of the job but a part of the job. He ended his address with the most important advice of all:

“Ease isn’t the goal; excellence is.”